19. Nature and Its Energy: Considerations on the Processes of Conserving Organic Matter

- Mercedes Isabel de las Carreras

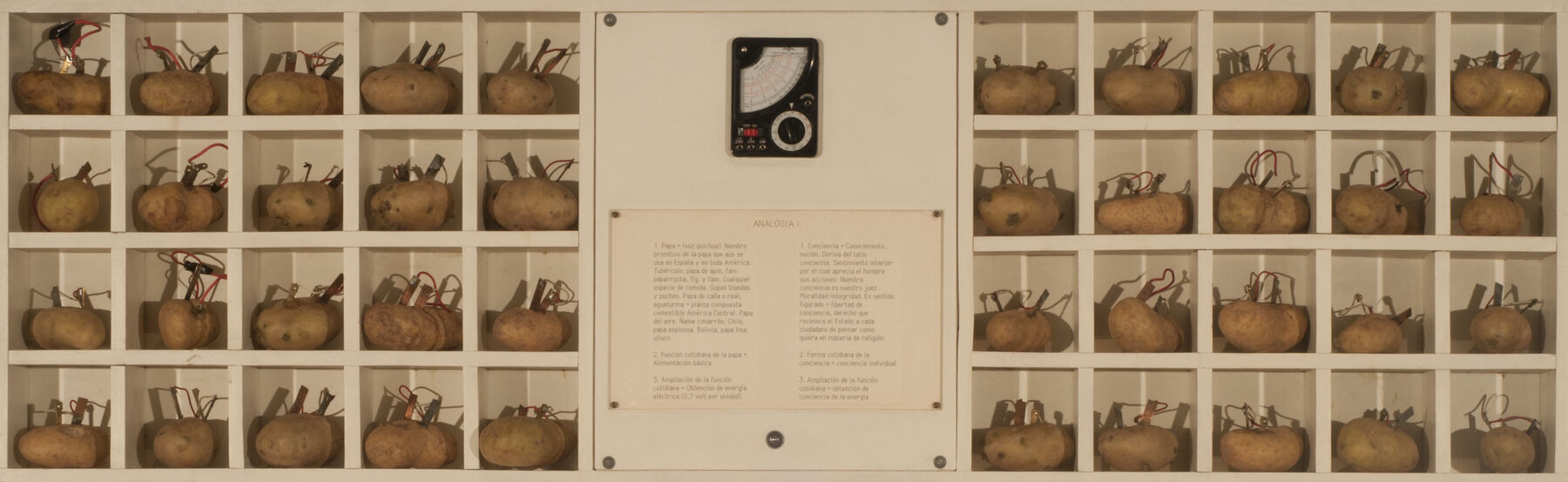

The Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Buenos Aires was inaugurated on December 25, 1896. The founding works came through donations from private collections. The museum’s first director, Eduardo Schiaffino, encouraged friends and collectors to give generously, and he visited Europe on buying trips with the mission to build out the collection. Over time, there have been significant additional legacies, acquisitions, and donations, and the collection nowadays, numbering around twelve thousand works, continues to grow while supporting the mission to disseminate the history of art from all periods. Víctor Grippo’s work Analogía I (Analogy I, 1970–71, fig. 19.1) was donated by Fundación Antorchas in 1990.1 The organic materials comprising the piece give it ephemeral characteristics and present specific conservation requirements that museum conservators had not previously needed to consider.

Figure 19.1

Figure 19.1Grippo was born in Buenos Aires in 1936.2 His education in chemistry, industrial design, visual communication, and fine arts brought about a convergence of art and science in his works. Finding his voice as an artist involved the creation of an innovative school of thought in which he gave new meanings to ordinary objects. His first paintings aligned with geometric abstraction and were done in oil paint. They were shown in his first solo exhibition in 1966. His greatest development as an artist occurred later, in the 1970s, when Buenos Aires’s political climate was conducive to intellectual stimulation and growth.

Analogía I was the first in his series of Analogías (Analogies), or “potatoes with wires,” as they are colloquially called. It consists of a circuit of forty potatoes, each placed in an individual cubicle in a wooden case, interconnected via small electrochemical means consisting of two electrodes, one copper and the other zinc, inserted into each potato. In this way, electrical current is obtained from each potato, and, linked together, they produce a total amount of direct current that is measured precisely and displayed via a central voltmeter. The mechanism measures the total energy output of the potatoes and provides an empirical demonstration of their energy capacity. The center of the structure also bears a text panel explaining the artist’s intended analogy between the potato as an object and consciousness as an intangible, thereby incorporating the viewer into his work as a conceptual participant. The work sets up dualities such as visible and invisible, tangible and intangible. It establishes an analogy between the potato and human awareness—between the meaning of each object, its daily function, and other possible meanings of that function.

Grippo’s motifs always centered on ideas of transformation, daily life, the world of farm labor, food, and the energy that food produces. The artist sought to produce power-generating processes through very simple material and technical resources such as the potato, which originated in the Americas and was subsequently cultivated around the world. The unconventional materials and media in his objects and installations reflect on the social and spiritual conditions of workers and artists. Considering that the potato is the most popular food in Argentina, consumed by all social classes, the poorest in particular, his choice was highly significant. Based on the potato’s cultural symbolism and the relationship between plant life, the soil, and farm laborers, using potato energy as an electrical battery expresses how humanity is transformed by engaging in a rural occupation related to the soil.

Grippo’s artwork also demonstrates the underlying power that is present in plant life and the energy that can be liberated by human creativity. It is an alchemical transfiguration of the material world from invisible to visible. The concept expressed is the result of the artist’s research in science and art, in which humanity is an essential medium in the symbolism of conceptual art. This type of work was characteristic of Grippo, and he developed it across different installations around the world.

This work in many ways falls under the umbrella of conceptual art, which swept the art world just as Grippo was finding his artistic voice. It invites the audience to find satisfaction in following the creator step by step through his thought processes, without asking that those processes take a concrete form. The underpinning ideas have precedence over its material or tangible aspects, favoring intellectual reflection over visual stimulation. The viewer participates in the process of formulating the concept, and follows the creative steps that comprise the idea. In this way, the artist’s constructive inquiries influence the viewer’s momentary conceptualization, and the idea prevails over the physical artwork itself.

In Analogía I, the ephemeral materials also speak of the transience of life—of the limited length of time in which matter undergoes a transformation and then disappears, leaving only the idea. Conservators become part of the maintenance of that idea by periodically changing the organic materials, which to some extent is a detriment to the concept of originality and uniqueness, demonstrating that, for the artist, the work exists within his intellectual process.

Since 1990, Analogía I has been exhibited at the museum several times.3 In terms of conservation, it has presented problems since its first installation. Potatoes are organic and deteriorate very quickly depending on their quality, environmental conditions, the amount of time that has passed since they were harvested, and the conditions under which they were transported. The potato peel is coarse and resistant, but thin, and if it breaks, decomposition accelerates. The internal liquids produced during decomposition ooze out through the weakest part of the peel, which takes on a dark color and bad smell over time (fig. 19.2, fig. 19.3).

Figure 19.3

Figure 19.3The conservation challenges are various, and so specific protocols to facilitate control of the work’s state of conservation for the duration of an exhibition were prepared. These cover procedures for installing the work, quality requirements of the organic matter, environmental conditions in the room, exhibition duration, and more. The protocols establish organized methodologies for conserving the organic matter and using staff resources prudently. The seemingly simple task of changing the potatoes on a regular basis requires funds and an interdisciplinary team of technicians and conservators to be regularly available at just the right time.

The protocols first detail all the procedures for installing the artwork. The painted wood structure is cleaned, and insulating material is placed in each cubicle to prevent the fluids exuded by decomposing potatoes from staining it.

Choosing the potatoes at the market is no minor task. Although there are no specifications from Grippo regarding which variety should be used, we do try to buy potatoes similar to those he himself employed, and we sometimes encounter certain difficulties in this choice due to variation in supply at the local market. Furthermore, empirical research conducted on the different qualities of potatoes based on their origins and physical history has enabled us to reach certain interesting conclusions. Among the supplies at the market we find potatoes of different colors, some scrubbed, some not, in a variety of sizes and qualities.

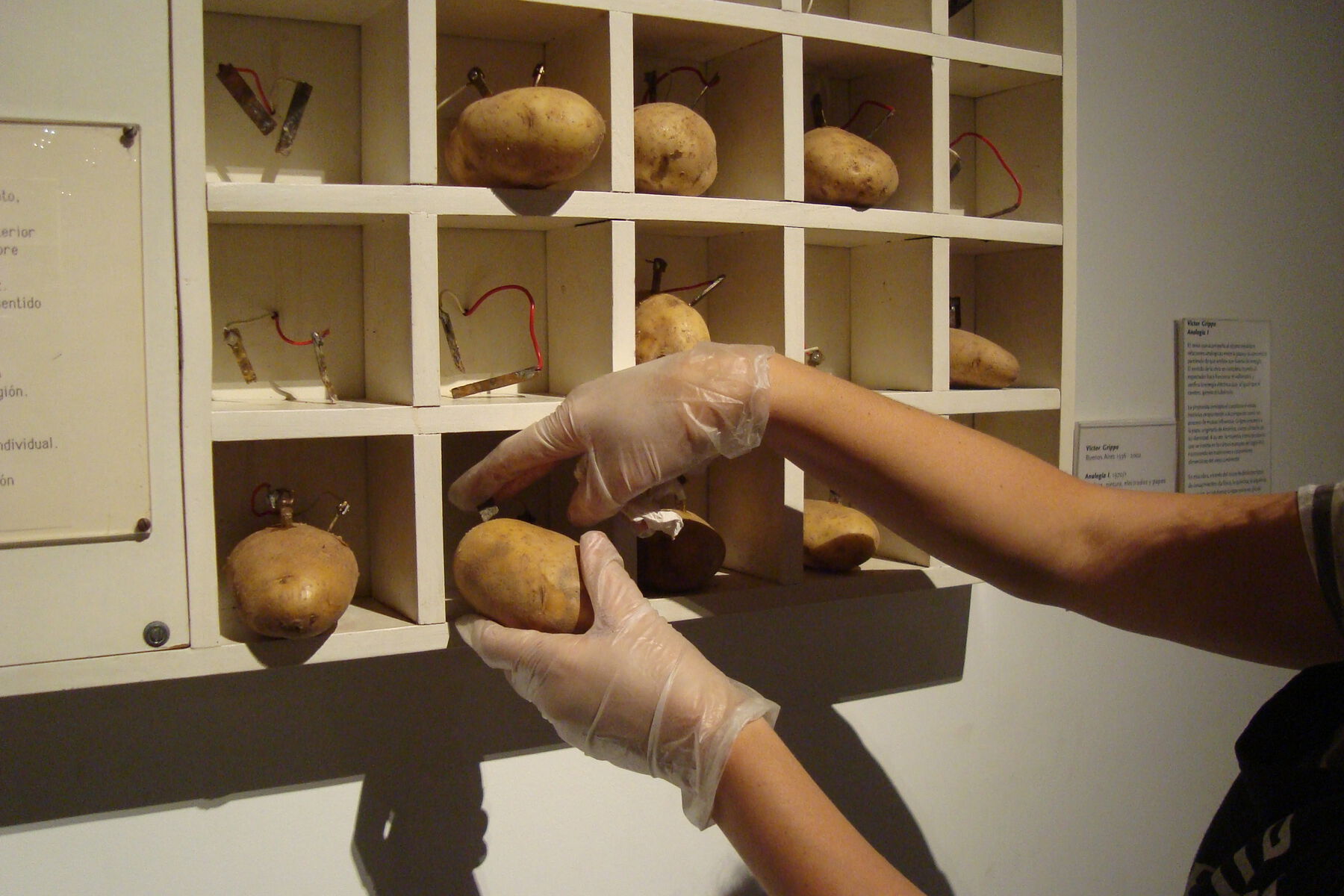

Conservation depends to a large extent on the potatoes’ quality and state of conservation at the time they are installed. They must all be of similar size so they will fit into the cubicles. The peel must be healthy, without cuts or sprouts growing. Any soil on them is removed with a soft cloth or brush, while avoiding injuring or dampening the surface, both of which accelerate decomposition (fig. 19.4). Purchase of the potatoes is ideally scheduled for the same day as the change-out in order to maximize the good condition of the organic material.

After the potatoes are installed, we confirm that each electrical connection is still functioning. The connection requires good contact between the cables and connectors in order for the total energy output to be measurable by the voltmeter (fig. 19.5). We periodically monitor the state of conservation of the living matter to confirm that it is functioning correctly. The experience of the conservator in observing the deterioration of the organic matter helps guide appropriate choices regarding when to change the potatoes, taking into account the time it takes to obtain new ones. Experience has shown that the potatoes must be changed every fifteen days or so in order for them to have sufficient energy to be measurable. Despite having protocols in place, conserving the work is still difficult due to the fragility of the system of electrical connections and the influence of the quality of the potato.

Figure 19.5

Figure 19.5Environmental conditions in the gallery space matter a great deal as well, since the damp, warm climate of Buenos Aires accelerates decomposition. In the most recent installation, the work was on view for a long period of time, during which more than ninety potatoes per month were purchased. If a particular collection rotation were to last two years, 2,160 potatoes and more than 120 conservator work hours would be needed to make the two changes per month (fig. 19.6, fig. 19.7). This has prompted conservators to occasionally consider possible alternatives that might save both financial and human resources, such as replacing the organic matter with something less perishable that would still produce electrical power, but sacrificing the aesthetic aspects was dismissed as a potential solution, despite the acknowledgment that the artist’s primary intent was the expression of his idea. It would change the piece too much. In the end, our valuation and appreciation of this piece of art warrants every effort of conservation. The compromise that was finally reached consisted of shortening exhibition durations and carefully planning the allocation of human resources.

Figure 19.7

Figure 19.7Notes

The museum’s web page devoted to the work is at https://www.bellasartes.gob.ar/coleccion/obra/9336/. ↩︎

Read more about the artist at the websites of the Centro Virtual de Arte Argentino (http://cvaa.com.ar/03biografias/grippo.php), Ludion (http://ludion.org/archivos/articulo/260411_rocha-margarita_v%C3%ADctor-grippo.pdf), Clarin (https://www.clarin.com/tema/victor-grippo.html), and Fundación Malba (https://malba.org.ar/sobre-vida-muerte-y-resurreccion-de-victor-grippo/?v=diario). ↩︎

As in Homenaje, a solo presentation staged on the ten-year anniversary of the artist’s death: https://malba.org.ar/evento/victor-grippo-homenaje/. ↩︎