7. Preserving Mortality through a Sacrifice for Your Country: A Performance by Carlos Martiel and a Conservator’s Challenge

- Flavia Perugini

The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, is one of the largest encyclopedic collections in the United States, holding about 450,000 artifacts ranging from ancient to contemporary art. It sees a very active program of exhibitions, loans, and tours, and occasionally collaborates with other institutions or collections on special exhibitions and events. In 2013 it partnered with the Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation (CIFO), a nonprofit organization based in Miami, to organize the 2014 exhibition at the MFA titled Permission to Be Global / Prácticas Globales: Latin American Art from the Ella Fontanals-Cisneros Collection. In early 2014, while preparing for the show, CIFO’s (now former) collection manager, Diego Machado, approached this author about preserving human skin for a piece that would be a part of an (unrelated) CIFO grant and commission program. He explained that the Cuban artist Carlos Martiel, one of ten artists participating in an upcoming exhibition titled Fleeting Imaginaries, intended to have a piece of skin removed from his body, preserved, and encased in a medal he had designed. Martiel, who had been planning this event as a performance for several years, only had six months to realize the plan and understood that the process required further study and specific steps to be followed. He had been advised to contact a taxidermist to help with the treatment, but he felt that taxidermy was not the appropriate approach. The request for collaboration was accepted, and research on the unfamiliar topic of practical live human skin preservation began.

The Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation

CIFO was founded by Ella Fontanals Cisneros in 2002 to promote and support Latin American contemporary art. The foundation serves as a platform for living Latin American artists through its many national and international programs, such as the Grants and Commissions Program, the Traveling Exhibitions Program, the CIFO Collection, and more. Fontanals Cisneros is CIFO’s founder and honorary president, and Liz Munsell, curator of contemporary art at the MFA, serves as a CIFO advisory committee member. To date, the foundation has exhibited the work of more than 130 Latin American artists and awarded grants amounting to more than $1.5 million.

CIFO’s 2013–14 Grants and Commissions Program explored the theme of displacement—literal, conceptual, and fragmentary, through fluctuation and transformation. Ten artists selected from a pool of applicants each received a grant to create an artwork that would be shown in Fleeting Imaginaries, running September 5 through November 2, 2014. The recipients were Pablo Accinelli (Argentina), Teresa Burga (Peru), Nayarí Castillo (Venezuela), Claudia Joskowicz (Bolivia), Marcellvs L. (Brazil), Carlos Martiel (Cuba), Mateo Pizarro (Colombia), Adrián Regnier (Mexico), Rosângela Rennó (Brazil), and Antonieta Sosa (Venezuela).

Carlos Martiel

Carlos Martiel (fig. 7.1) was born in 1989 in Havana. In 2009 he graduated from the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes San Alejandro, and between 2008 and 2010 he studied under the guidance of Cuban performance artist Tania Bruguera. Since 2007, Martiel, who currently lives between New York and Cuba, has performed extensively in the Americas, Cuba, Europe, and North Africa. He has participated in many biennials, such as the Venice Biennale, and performed in many important museums and galleries. Martiel’s work highlights social, economic, and racial matters, such as discrimination, migration, and power relations. In his performances the artist subjects himself to extreme physical and psychological conditions. Blood and skin piercing are common in many of his performances, and so having a piece of skin removed from his body was an extension of this practice and did not seem unusual for the artist.

Figure 7.1

Figure 7.1Martiel had originally planned this project back in 2010, but due to logistical complications, on that occasion he ended up performing a work titled Prodigal Son, in which he pinned medals his father had earned through military achievement onto his bare chest. Both the 2010 and the rescheduled 2014 performances were intended to illuminate Cuba’s racial problems, specifically its systemic and institutional racism toward Afro-Cubans.1 Despite Fidel Castro’s attempts to end racial discrimination at the end of the 1950s, it continues to affect people of color in Cuba; they are ostracized and/or segregated and lack social supports. In this 2014 work, Martiel would “award” himself a gold medal similar to those given by the government to state officials and the military, such as his father.

Research

While researching for this project, it soon became evident that medical professionals don’t commonly assist artists who want to use their bodies in such a manner. Many universities and medical facilities in the Boston area were contacted for advice on the preservation of human specimens, but little to no information was gathered; indeed, some commented that, in their opinion, the artist was irrational and attempting something that no medical professional should get involved with. The Hippocratic oath involves swearing “to treat the ill to the best of one’s ability,” and thus, the prospect of a healthy patient wanting a piece of healthy skin surgically removed and desiccated for an art project would be inappropriate, even unethical.

Meanwhile, internet research yielded different and more useful results. Medical articles revealed that since the nineteenth century, doctors around the world have been involved with skin removal to preserve tattoos, albeit from deceased people. Today many museums associated with hospitals and universities host collections of tattooed skin, not all of which are for medical research purposes. A query was posted on the Global Conservation Forum—at that time called the Conservation DistList—in hopes of acquiring more relevant advice. Surprisingly, an inundation of replies from professionals such as conservators and biologists who had worked on skin or were familiar with processing human specimens provided the necessary directives.

Skin Preparation Techniques

Skin preparation is executed in different manners, depending on factors such as whether the skin is of human or animal origin, and whether the whole body is available or only parts of it (). Mummification is one method that has been practiced in several countries since early civilization. The procedure consists of exposing a body to drying elements such as salts that absorb water from the body and desiccate it (). The desiccated bodies remain susceptible to moisture in the environment. Mummification was not considered appropriate for this project due to the lack of control over the specimen’s results and the length of time the process requires.

In the case of treatment of animal skin, any of the following three methods may be employed: taxidermy, tanning, or rawhide (). Taxidermy is a process that preserves an animal’s exterior body. The animal skin, with fur or feathers, is separated from the flesh and bones and then stuffed to give shape back to the body. Tanning is used for leather production, whereby a skin undergoes exposure to many liquids and extensive manipulation; it involves salting, soaking, liming, un-hairing, de-liming, and/or pickling. Liming involves extensive alkaline baths to remove hair, fat, and flesh and soften the skin, followed by acidic baths for the purpose of neutralization. Production of rawhide consists of removing the skin from the animal body and stretching it over a frame for air drying. This process is also used to make parchment. These three treatments leave the dehydrated skin reactive to moisture and susceptible to biological degradation.

The treatment of human tissues differs from that of animal tissue and may involve plastination, freeze-drying, or solvent drying (). Plastination involves fixing a human specimen in formalin (a preservative for human and animal tissue specimens that prevents degradation and mold formation), followed by flooding it with acetone, and subsequently impregnating it with polyethylene glycol (PEG), silicon rubber, polyester, or other polymers. This system is typically used by embalmers and achieves long-lasting results (). Plastination is the only method that renders the skin a little more resistant to humidity, although it doesn’t completely protect from mold growth. Freeze-drying is carried out with a process called lyophilization: the specimen is gently frozen and water is extracted in the form of vapor using a high-pressure vacuum. A gradual temperature rise extracts all remaining “bound” moisture from the specimen. This treatment is also used in conjunction with taxidermy. The main drawback to this method is that a dried specimen remains very susceptible to fluctuations in relative humidity. In solvent drying, the skin is separated from flesh and fat to reduce the possibility of putrefaction. After fixation in formalin, the tissues are bathed in a drying solvent solution that is adjusted daily until all water has been removed.

Solvent drying was ultimately selected for the treatment of Martiel’s skin, due to its ease of execution and affordability.

Experimentation

With only one chance to remove a piece of skin and succeed in its dehydration, experimentation was necessary to understand the physical behavior of skin removed from a live body. For practical reasons, the experiments were carried out on animal skin. Pig skin has similar characteristics to human skin, and was therefore selected. Arrangements were made for the conservator to visit a local farm on a day when pig slaughtering was scheduled. Suitable skin was identified on the necks of three pigs, which varied in color. Following slaughter, the skin specimens were extracted and placed in a glass container with distilled water for transportation in a cooler. Upon arrival at the conservator’s studio, the skin was rinsed in fresh distilled water and small sections were cut for the experiments. For safety reasons, formalin was not used in this instance due to its toxicity, although it would be used to preserve the final human specimen. The outlines of these skin samples were marked on paper to track any dimensional changes that might occur during the tests.

Over the course of ten days, the skin was bathed in a distilled water and ethanol solution that was changed daily to facilitate the drying process. Afterward the pieces of skin were cut into smaller sections and allowed to slowly air dry in a controlled environment. The edges were stapled onto a plain cardboard support covered with a sheet of Volara, a closed-cell polyethylene foam, to prevent curling or warping.2

These experiments were repeated three times to ensure consistency in the results. After drying, consistent shrinking in all directions was observed and calculated at around 1 or 2 percent. This information was shared with the artist in preparation for the surgery.

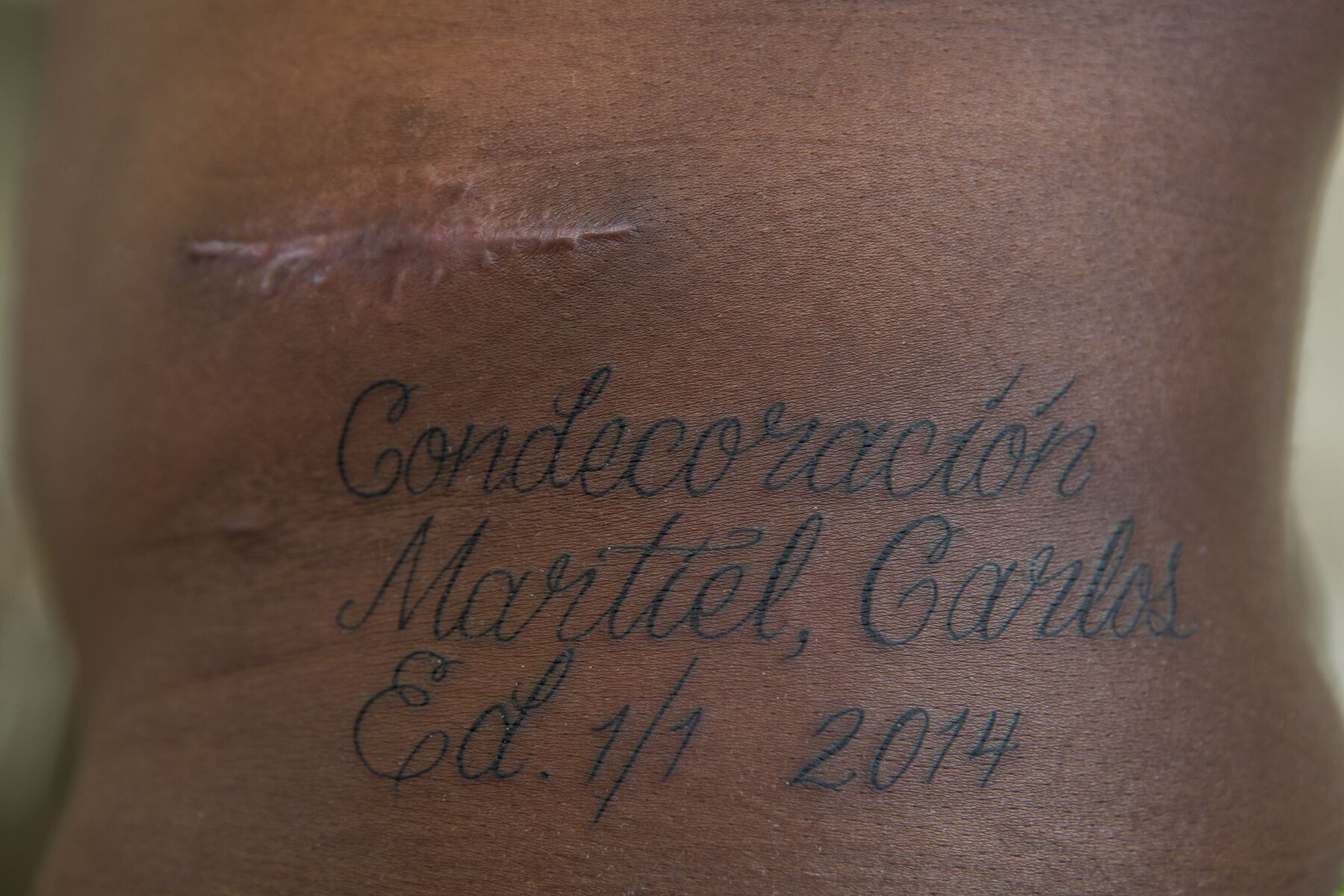

With this new information, the artist revised his initial idea of having a tattoo removed and dehydrated; given the small size of the medal that would contain the specimen, Martiel realized that the shrinking of the skin would make the tattoo illegible. He decided to have an un-tattooed piece of skin removed and to get a new tattoo consisting of the title of the work—Award Martiel, Carlos—applied after the surgery, near the scar.

The Surgery and Skin Treatment

With a clear list of appropriate steps required to execute this project and a timeline in place, the surgery was scheduled for July 9, 2014 (fig. 7.2). The event was filmed and photographed by Daniel Godoy, a professional filmmaker and producer. Godoy also filmed an interview with the artist for a possible documentary on art and social issues.

Figure 7.2

Figure 7.2Doctor Flor Mayoral, professor in the Department of Dermatology and Cutaneous Surgery at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, was selected to perform the surgery. An artist herself and a friend of Fontanals Cisneros, Mayoral was interested in the project and actively participated in the conversations with the conservator throughout the process. Knowing that the medal was 45 mm in diameter, she marked Martiel’s skin on the left side of his waist accordingly. The area of the incision was selected based on Langer’s lines, which determine where a surgeon should cut the skin to obtain the least invasive scarring and optimal healing.3 The measurement was determined by considering the shrinking of the skin upon removal from the body, as well as the age of the patient; being in his early twenties, he had healthy and very elastic skin. It was calculated that after surgery the skin would shrink at least 1 percent, and about the same amount or a little more after drying.

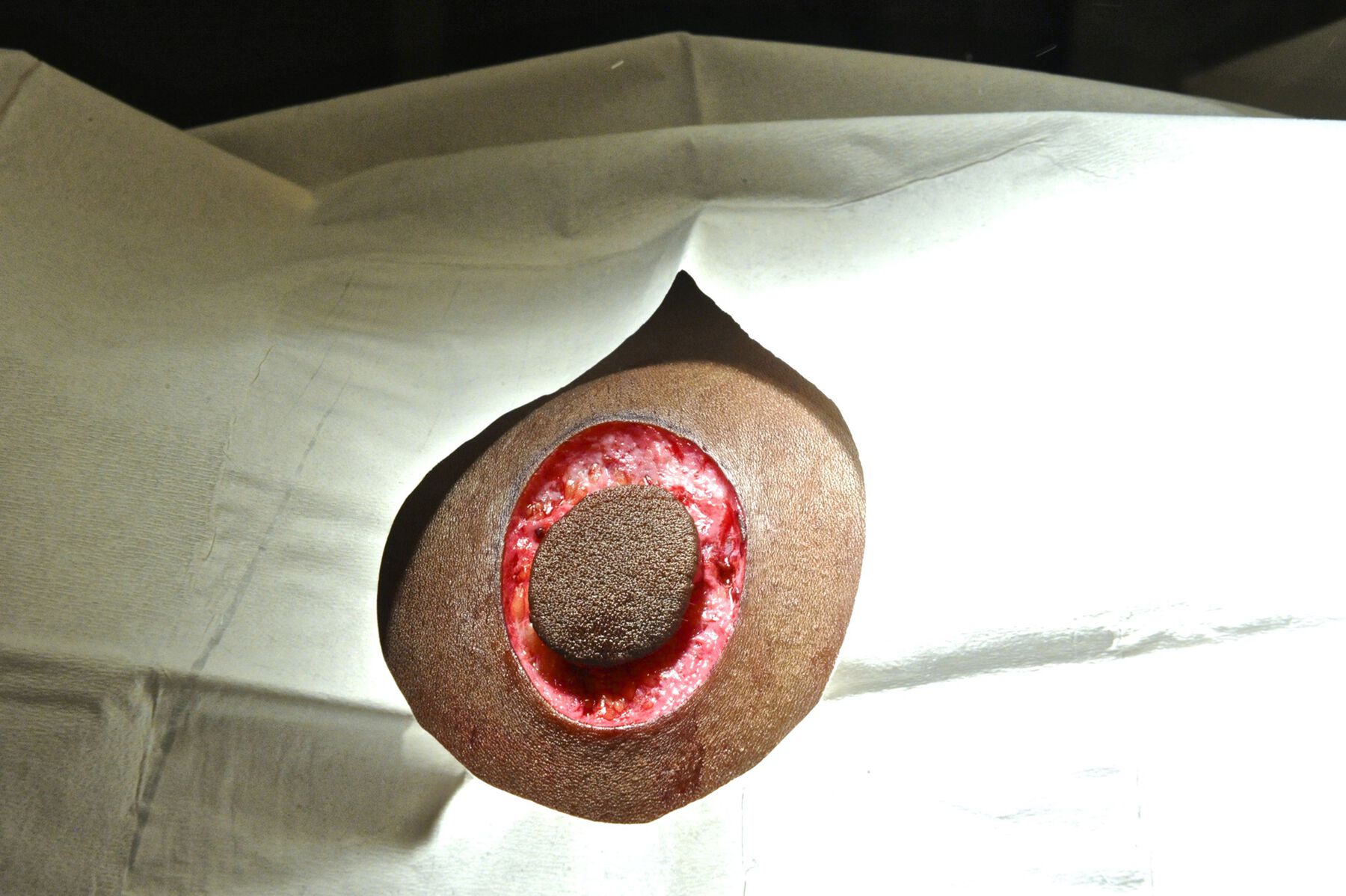

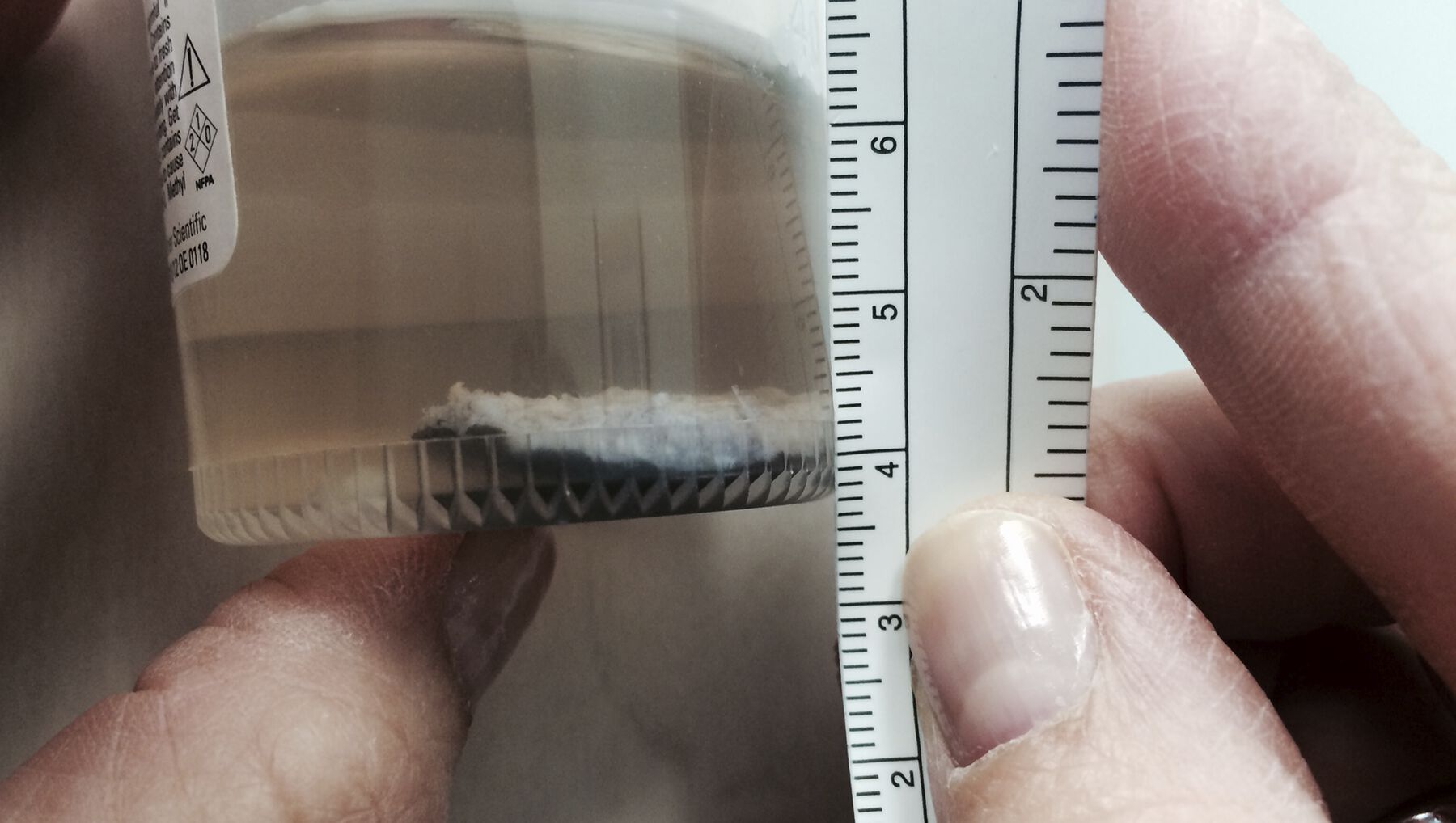

Upon removal (fig. 7.3), the piece of skin was cleaned with a scalpel to remove deposits of fat, which would have encouraged putrefaction and thus compromised the desiccation and preservation of the specimen. The piece of skin, which measured about 3 mm in thickness (fig. 7.4), was placed in a sterile cup containing formalin. After twenty-four hours, the specimen was removed from the cup, rinsed in distilled water, and placed in a new sterile container with distilled water and ethanol. This solution was replaced daily over the course of ten days.

Figure 7.3

Figure 7.3 Figure 7.4

Figure 7.4The specimen appeared oval in shape. This was likely due to the fact that the marking on the skin had been carried out with the artist standing up, and the marked circle had become distorted when he lay down on the operating table. Overall, the width of the specimen was about 40 mm at the largest point and about 35 mm at the narrowest.

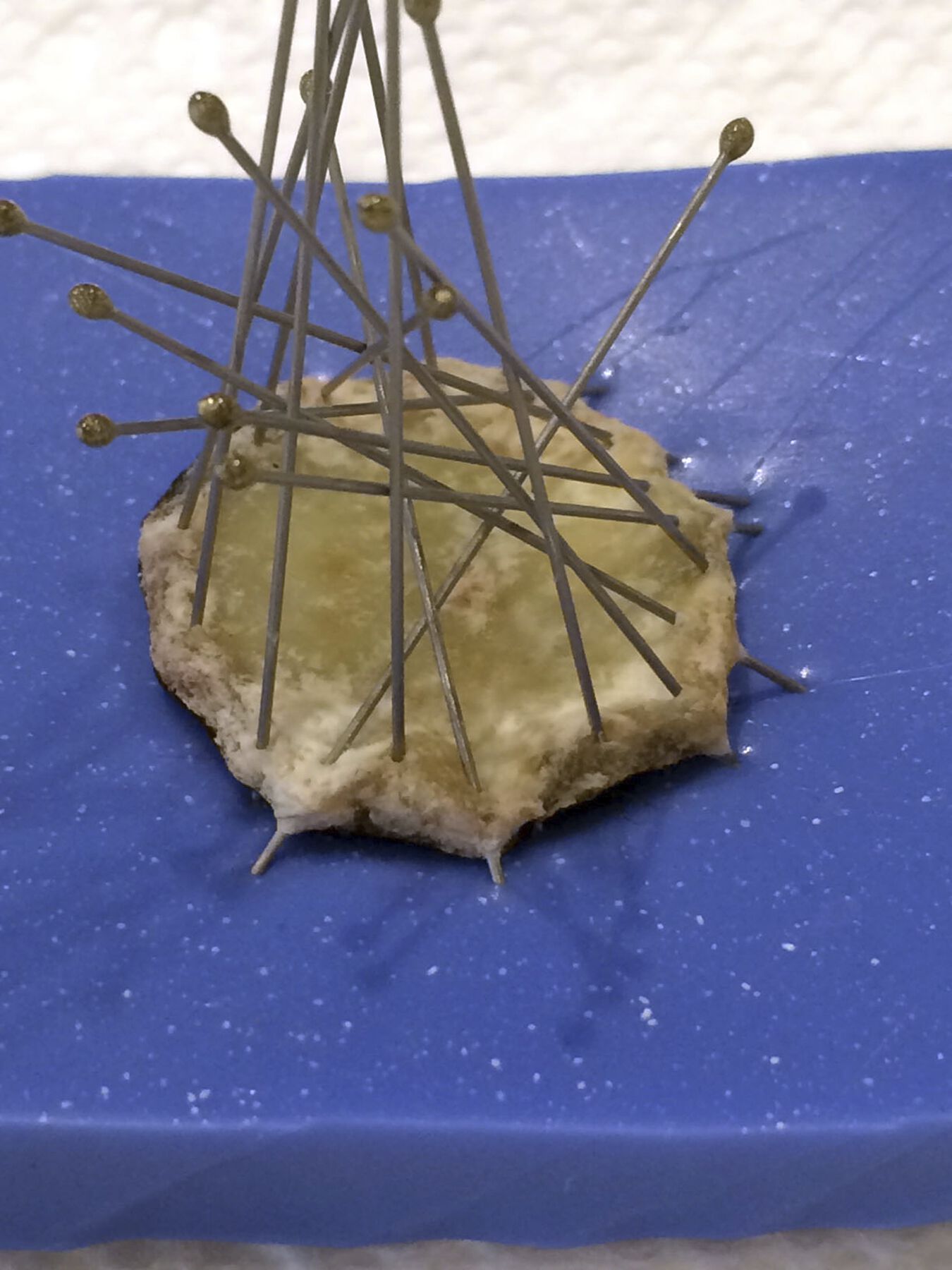

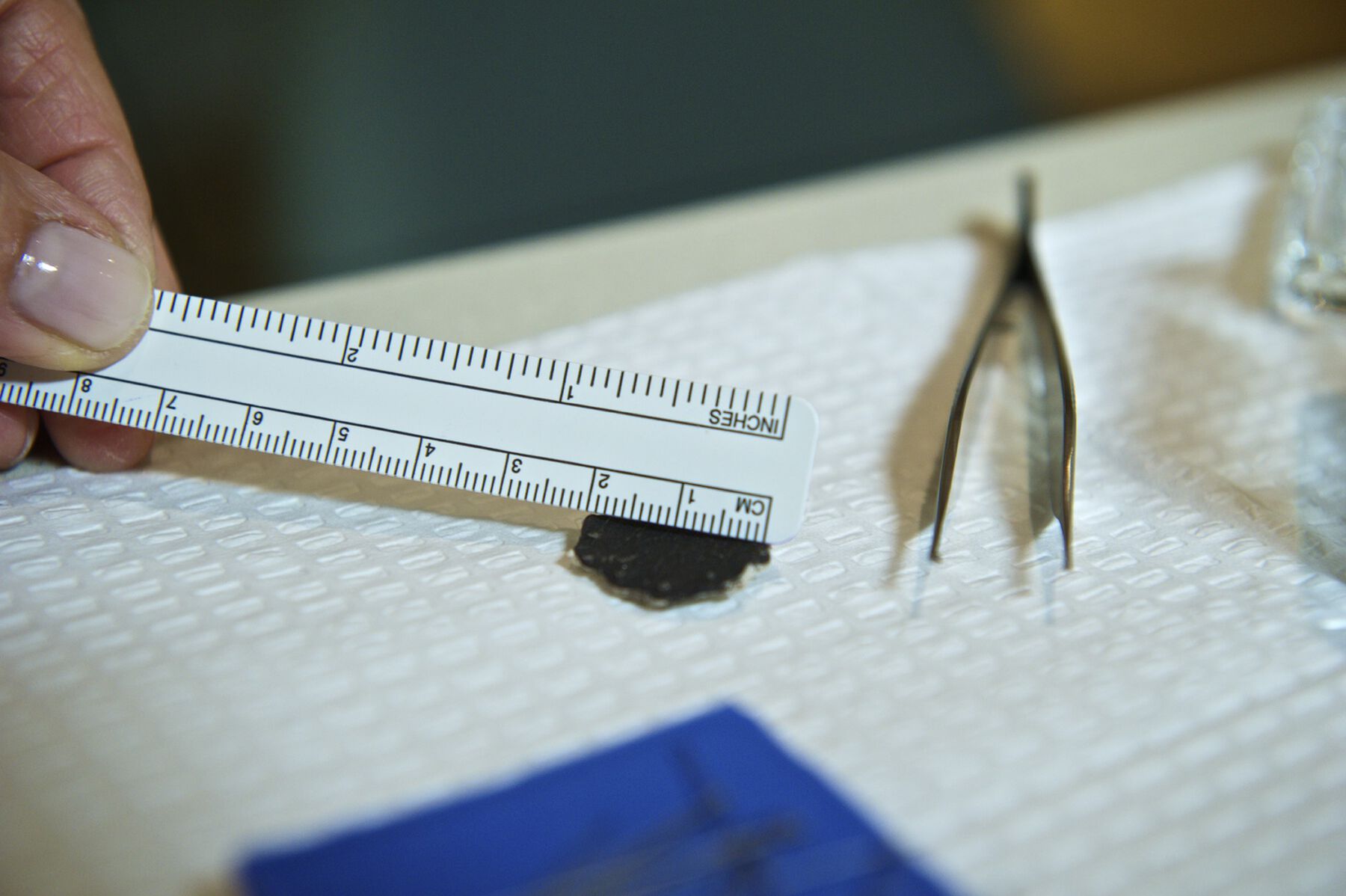

After bathing, the piece of skin was prepared for the slow air-drying process (fig. 7.5). The specimen was placed face-down onto a biological mat and pinned in place with entomology steel pins, slightly pulling out the edges to gently restore a circular shape, which proved successful.4 After drying, the specimen appeared darker in color and smaller in size (fig. 7.6) as predicted, and measurements confirmed the desired size of 20 mm in diameter (fig. 7.7).

Figure 7.5

Figure 7.5 Figure 7.6

Figure 7.6 Figure 7.7

Figure 7.7The specimen was inserted in the medal just in time for the opening reception of Fleeting Imaginaries at CIFO, Miami, on September 5, 2014. The final work, titled Award Martiel, Carlos, comprised the medal containing the skin (fig. 7.8), a video of the surgery, and an image of the artist’s scar and tattoo (fig. 7.9). At the end of the show, the medal containing the skin was packed in archival materials and retired to the CIFO’s environmentally controlled storage facilities.

Figure 7.9

Figure 7.9Conclusion

Martiel’s performance was originally planned in 2010 but not executed until four years later due to a lack of resources and information. Communication between the artist, CIFO’s staff, the conservator, the surgeon, and many other parties was extensive and highlighted the need for everyone to be in conversation at all times. The artist’s wound healed well and the skin was successfully preserved. Through this performance, Martiel used his CIFO grant to shed light on the social effects of segregation in Cuban society. By placing a piece of his skin into a gold medal, he highlighted the importance of Afro-Cuban influence in Cuba’s social structure and provided a platform for Afro-Cuban artists.

The preparation of biological specimens is complex and requires a clear understanding of the available processes, the behavior of the specimen, and the characteristics of the results. Without extensive research, conversations with several professionals, and numerous trials, the project would likely not have been possible. The conservator’s involvement, which began with thorough research and practical experiments, allowed for the most appropriate skin preservation method to be selected, and for more control over the dehydration of the skin. Close collaboration between the conservator and the surgeon was crucial in the calculation of the size of the skin specimen to be removed, as well as in the treatment of the specimen, in order to obtain the best results.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Martyn Cooke, head of conservation, Royal College of Surgeons of England, UK; Jesse Meyer, Pergamena, Montgomery, New York; Emily O’Reilly, principal conservator paper, National Museum of Wales; Éloïse Quétel, conservator-restorer of ethnographic objects, France; and John Simmons, adjunct curator of collections, Penn State University.

Notes

Martiel is Afro-Cuban. His father was able to join the army and get decorated for his merits, a particularly honorable matter for a Black Cuban. With this work Carlos sacrificed his skin for his father and for the country in an attempt to assert his place in Cuban society. ↩︎

For more information on Volara see http://www.paccin.org/content.php?275-Volara-Crosslinked-Polyethylene-Foam. ↩︎

A good summary is at Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Langer%27s_lines. ↩︎

A typical mat is pictured here: https://www.carolina.com/dissecting-pans-pads/vinyl-dissecting-pads/FAM_629006.pr. ↩︎

Bibliography

- Brenner 2014

- Brenner, Erich. 2014. “Human Body Preservation: Old and New Techniques.” Journal of Anatomy 224 (3): 316–44. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fjoa.12160.

- Grantz 1969

- Grantz, Gerald J. 1969. Home Book of Taxidermy and Tanning. Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole.

- Kite and Thomson 2006

- Kite, Marion, and Roy Thomson. 2006. Conservation of Leather and Related Materials. Boston: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Knoeff and Zwijnenberg 2016

- Knoeff, Rina, and Robert Zwijnenberg, eds. 2015. “The Fate of Anatomical Collections.” Special issue, Social History of Medicine 29 (4).

- Quigley 2015

- Quigley, Christine. 2015. Modern Mummies: The Preservation of the Human Body in the Twentieth Century. Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

- Spindler et al. 1996

- Spindler, Konrad, Herald Wilfing, Elisabeth Rastbichler-Zissernig, Dieter ZurNedden, and Hans Nothdurfter, eds. 1996. Human Mummies: A Global Survey of Their Status and the Techniques of Conservation. New York: Springer Science and Business Media.