14. Research, Conservation, and Exhibition of a Contemporary Art Installation Containing Living Organisms as Part of the Creative Process

- Claudia Barra

- Cristina Bausero

- María Pía Cerdeiras

- Silvana Alborés

- Belén Estévez

- Soledad Martínez

The collections of the Museo Juan Manuel Blanes (fig. 14.1) in Montevideo, Uruguay, initially consisted of donations and acquisitions by the city of Montevideo. Starting in 1940, these were supplemented by acquisitions of prizewinning works from the Salones Municipales (Municipal Exhibitions), which brought in pieces by the more renowned Uruguayan artists of the twentieth century, such as José Cuneo, Carmelo de Arzadun, Alfredo De Simone, Amalia Nieto, Joaquín Torres García, Eduardo Yepes, María Freire, Miguel Ángel Pareja, and Hilda López, to name a few. Their works generally employed traditional techniques such as oil on textile support or on wood, drawings in graphite or ink, watercolor on paper, or sculpture in marble, bronze, wood, or plaster. As the twentieth century unfolded, many works began to be created using cardboard as a support, notably by Joaquín Torres García and his fellows in the Escuela del Sur (Southern School), Pedro Figari, and others. The pictorial language evolved as well from figurative to abstract, covering a wide range of expressions. Screenprinting appeared in the 1950s and 1960s, and left a strong mark on Uruguayan art. In the mid-twentieth century, works of art using new materials and formats such as video art, installations—and, importantly for our discussion here, biological material and digital art—entered the museum’s collection.

Figure 14.1

Figure 14.1Contemporary art requires that we consider traditional concepts of conservation, deterioration, and sustainability in a new light, in which the artist’s intent and the functionality of the objects often take on crucial roles. With this in mind, new challenges in their preservation must be faced, ranging from aspects of the infrastructure required for storing large-format works to the preservation of new materials, novel combinations of elements, including objects originally intended for industrial or domestic use, and new requirements for the preservation of immaterial functionality and content. Knowledge of the artist’s intentions and an interdisciplinary approach are required to establish criteria for registering and documenting works and for storage and exhibition.

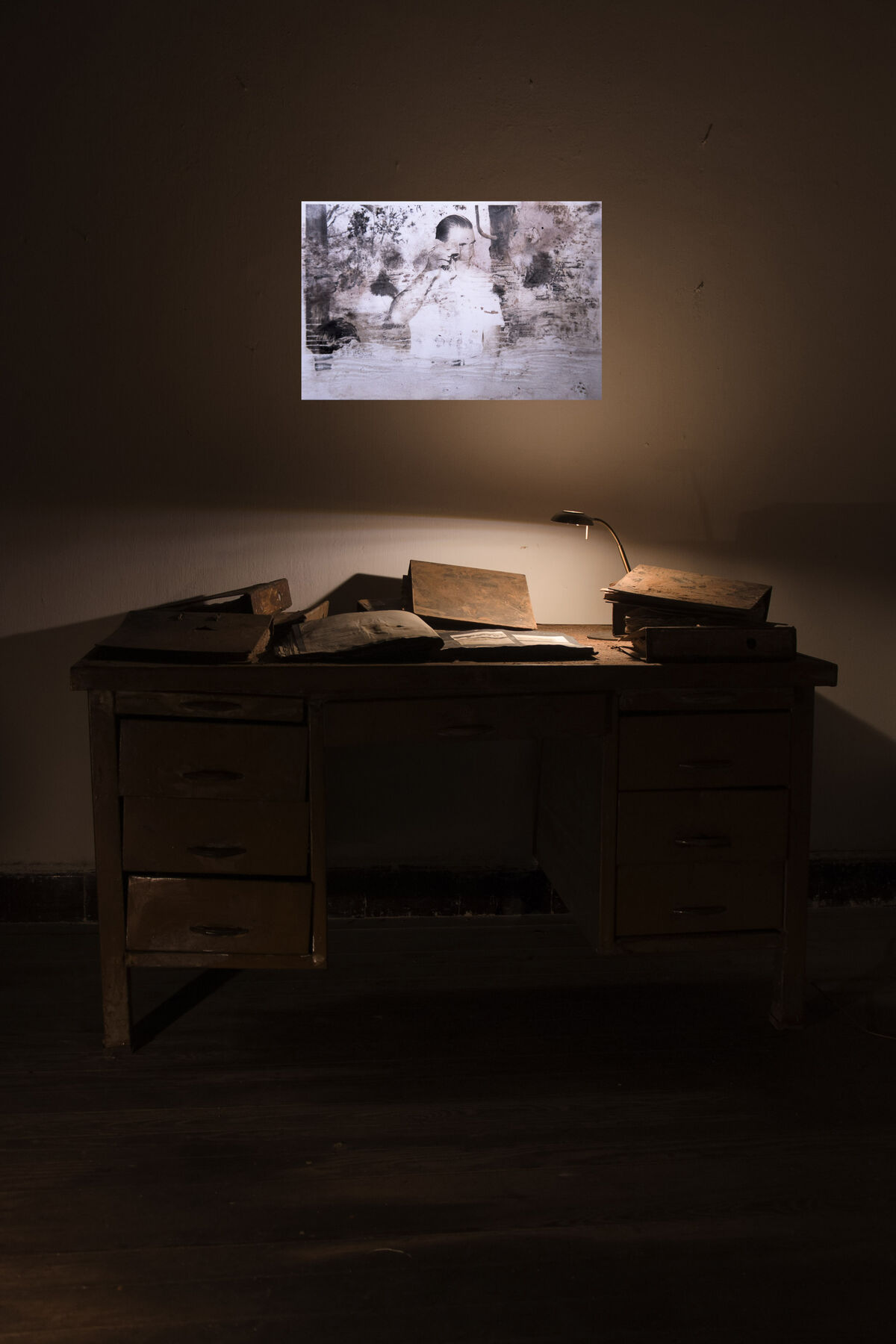

The installation Lo que mata es la humedad (It’s the Humidity That Kills, 2017, fig. 14.2, fig. 14.3) by Uruguayan artist Federico Arnaud (b. 1970) won Second Acquisition Prize in the Montevideo city government’s 2017 Premio Montevideo competition (the new name for the Salones Municipales). The installation consists of a metal desk with a swivel office chair and a portable lamp, which directly illuminates a photograph album and nine binders.1 The desk has a surface layer of dirt that was applied by the artist in the form of mud. Dirt also covers the outsides of the binders and the other elements, with the exception of the album. A video is projected on the wall behind the desk, showing photographs from the album in slide format. An audio track accompanies the imagery in the video; the sound of a working slide projector bursts with each new image that appears.

Figure 14.2

Figure 14.2 Figure 14.3

Figure 14.3The installation testifies to the military dictatorship in Uruguay, which is conveyed in the album’s photographs showing military and political leaders from the period. In the artist’s own words: “There is a silent violence in the images that is being lost to the mold of humidity” (, 28–31). Arnaud is alluding to a parallelism between the idea of the deterioration of those who played a part in that period and the deterioration of the photographic evidence. As digitized in the video that is part of the installation, these images are preserved, thus safeguarding a testament to those times.

Conserving the Installation

Once the primary technical and photographic records of the installation were made, an evident need emerged to utilize new criteria in recording, documenting, and conserving it. The artist was invited for an interview for the purpose of hearing his thoughts regarding the future conservation of the work and to prepare protocols for mounting it for exhibition. These interviews revealed the express need to keep alive the microorganisms that were contributing to the deterioration of the photographs in the album, of the cellulose material contained therein, and of the binders. Research on these aspects was thus begun after assembling an interdisciplinary team. Docents specializing in photographic conservation were called in from the Centro de Fotografía de Montevideo,2 and studies of microbiological contamination were carried out in collaboration with specialists from the Universidad de la República.3 The documentation and records team worked with the conservation team to prepare an identification file (also called a unique object record) and enter it into the museum’s digital database. A report was prepared on the installation’s state of preservation and the requirements for preserving it while in storage and when exhibited.4

The interview required that the artist acknowledge the difficulties of conserving the work and the risks entailed in its conservation. He was also informed of the need to research new conservation strategies by which materials in the installation containing microorganisms would be conserved (namely, at low temperatures).5 The interview led to a protocol of documenting the artist’s intentions and a proposal for mounting, in which the artist stated: “I admit that I am aware that the photograph album is affected by mold that will eventually obscure the images. I feel it is useless to attempt its conservation because the meaning of the work is that the memories it contains are disappearing due to the circumstances of their abandonment, and that that has material and political consequences.”6

Microbiological Study of the Work and Its Surrounding Environment

The objectives of the museum’s plan for preventive conservation and a program of scientific research include a plan to determine the level of microbiological contamination present in both the photograph album and the binders, and in the environment of Store F, where the work resides when not on view.7 Specific objectives include isolating and identifying the mold species present in and on the photograph album and binders, and the mold species present in the environment surrounding the installation. The investigation included determining whether there is any correlation between the microorganisms present in the room and those present in the installation’s elements under study, as well as understanding the pathogeny of the species found.

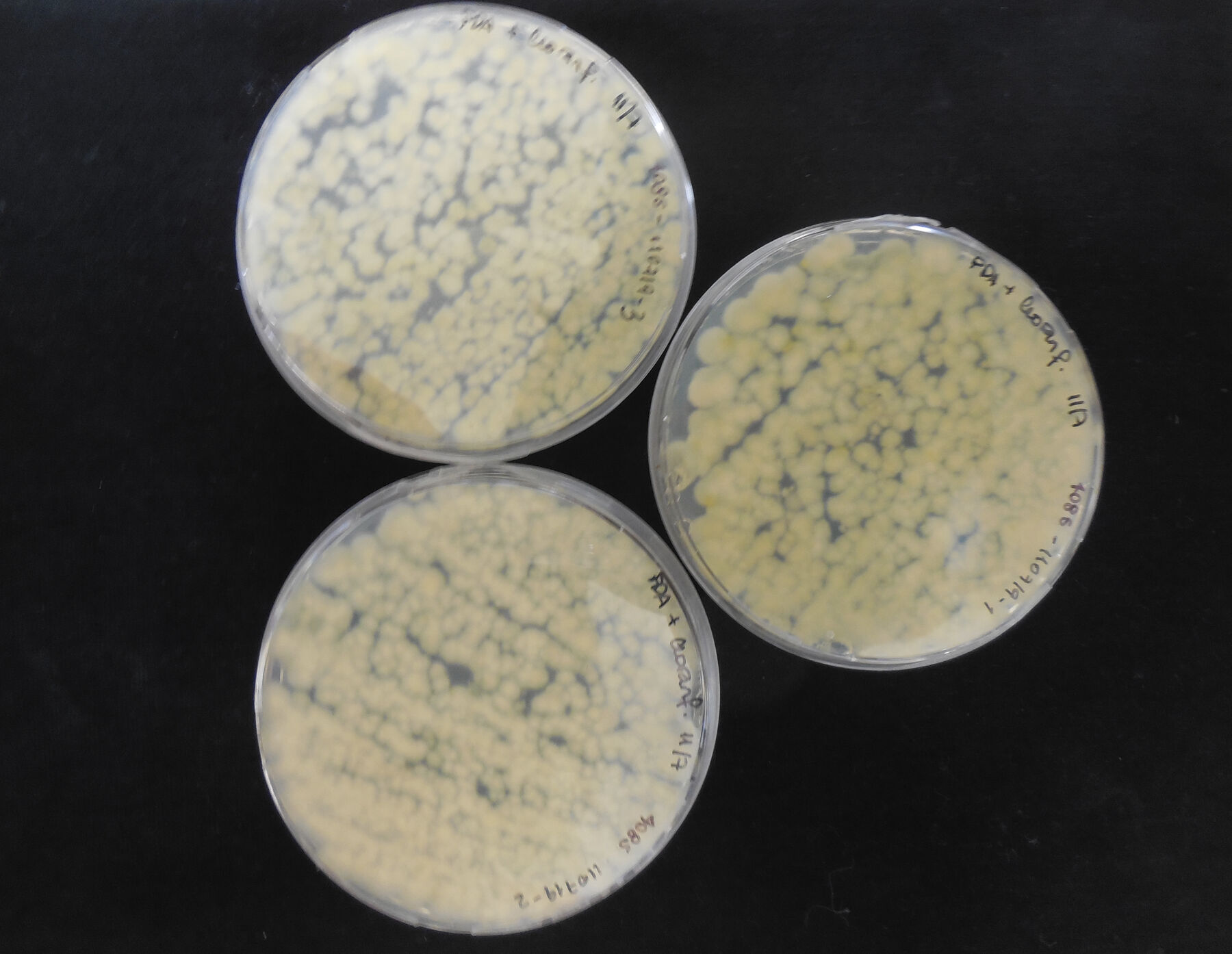

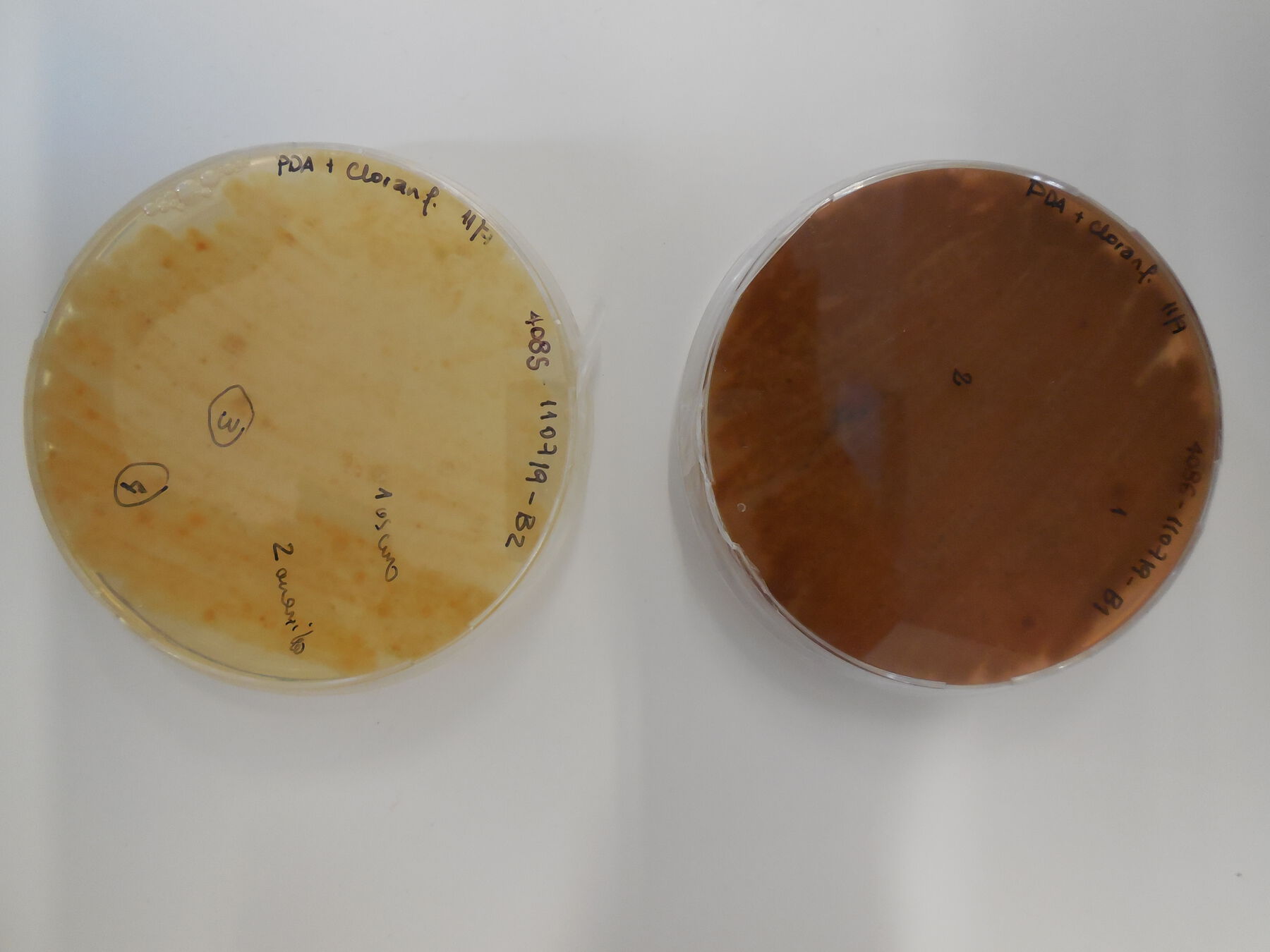

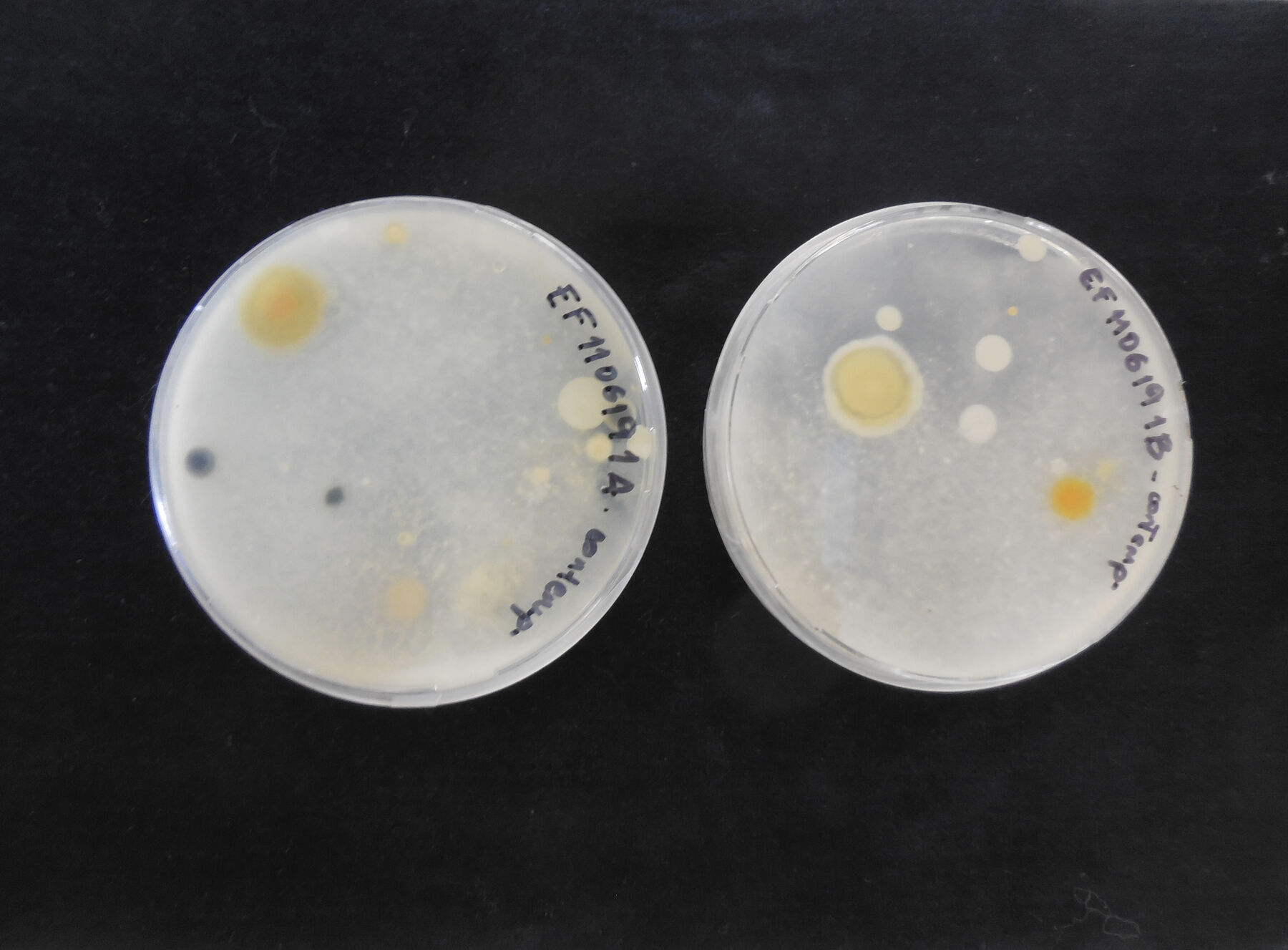

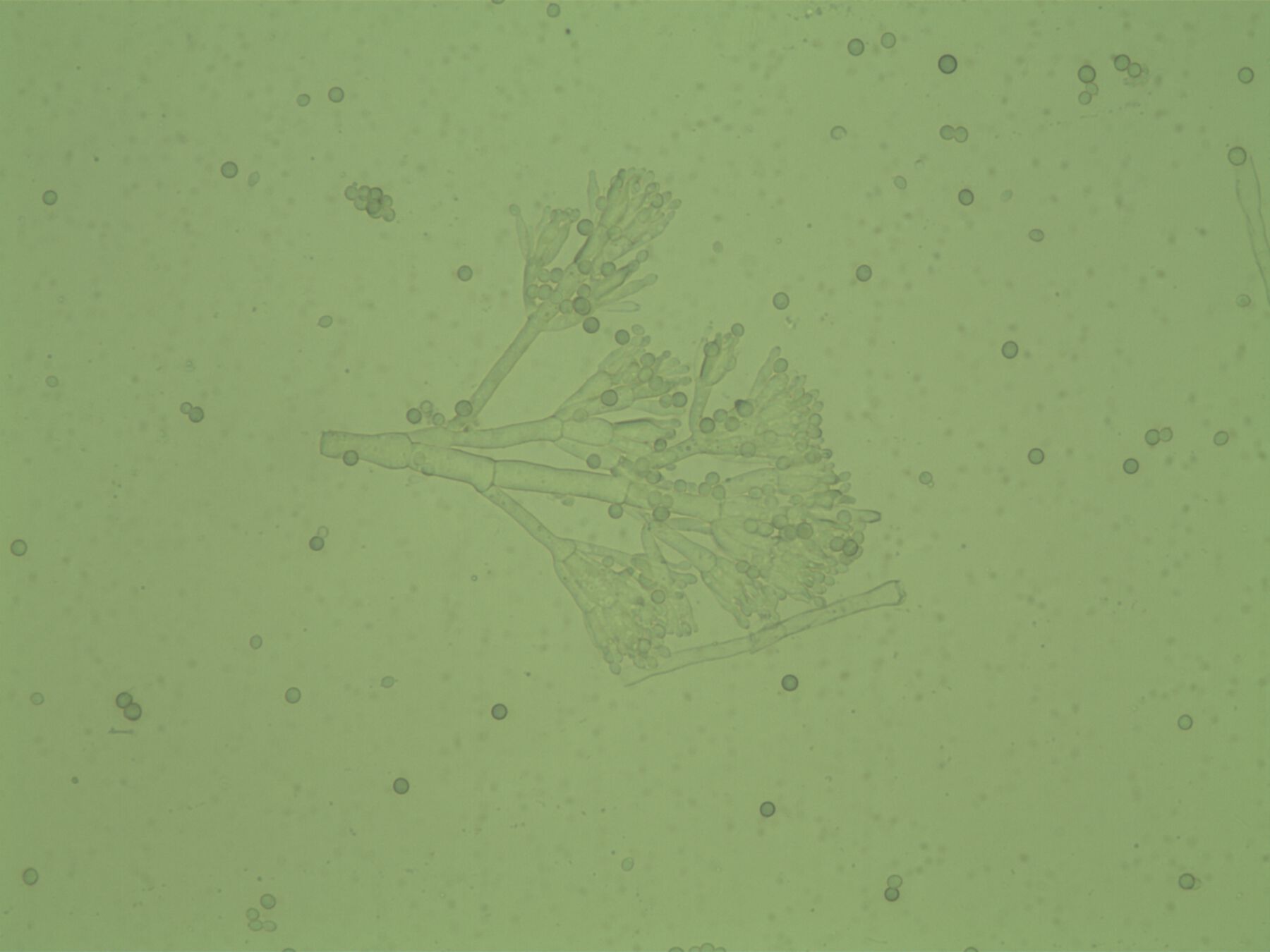

For the study, samples were taken from three photographs from the album and the exterior surface of one binder. The samples were taken in the museum, in triplicate, using sterile commercial cotton swabs minimally dampened with physiological saline solution, sampling areas where the presence of mycelium and stains, apparently from mold contamination, were observed (fig. 14.4). The swabs were immediately put into test tubes with NaCl 9 g/L (physiological serum) for transportation. In the laboratory, the samples were inoculated in petri dishes with potato dextrose agar (oxoid) (PDA) with chloramphenicol and incubated at 25°C, in the dark, for five days. After the growth period, to obtain pure cultures, three petri dishes with PDA were inoculated consecutively and incubated at 25°C for five days. In the cases in which isolated colonies were not obtained, monosporic cultures were performed, making adequate dilutions with spores of the mold under study, introducing them into the PDA and incubating them at 25°C for five days (fig. 14.5, fig. 14.6, fig. 14.7).

Figure 14.5

Figure 14.5 Figure 14.6

Figure 14.6 Figure 14.7

Figure 14.7At the same time that samples were taken from the components of the installation, samples were also taken from the surrounding environment of Space F. The environmental conditions during the sampling were 16°C and 58 percent relative humidity, during the winter season. This was done by placing open petri dishes with the PDA culture medium containing chloramphenicol in the room for thirty minutes. The number of dishes set out was based on the area to cover, and they were placed in duplicate (fig. 14.8).

Figure 14.8

Figure 14.8First the genus was identified through observation of the macro- and micro-morphological characteristics of the colonies, following the keys according to J. I. Pitt and R. A. Samson (; ; ). Fresh samples from the isolated colonies were examined under a Nikon ECLIPSE E200 microscope with a digital Y-TV55 camera. From the set of six samples taken from the objects, species corresponding to the Penicillium genus were isolated based on their morphological characteristics (fig. 14.9). Since they could be seen with the naked eye, a high number of fungus colonies were isolated from the objects. Confirmation of the presence of species of the Alternaria genus on the samples from the binder is still pending.

Figure 14.9

Figure 14.9Although the researchers have not yet obtained final results, they were able to observe that the fungi isolated from the room environment did not match those isolated from the installation’s components. The result of the samplings from the room environment was promising: the number of colonies that deposited on the dishes within the thirty minutes of exposure was not high.

The genera of fungi found so far are the usual agents of deterioration in organic materials. They proliferate in enclosed, damp places with low air ventilation. They are in the air and on the floor, and they disperse through spores. The risk for contamination of different materials can be evaluated in relation with water activity.8 Different ranges of this parameter have been reported that are linked to the growth of fungi (, 2). The method chosen for identifying the species was amplification and sequencing of the rDNA of ITS1 and ITS2. (These studies were done outside the country, along with another group of environmental samples that were taken from the museum’s collection.) The sequences obtained will be entered into the appropriate software that will identify them by comparing them to fungus nucleotide sequencing reports from the database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) using the BLAST tool.9

Once we know for certain the species of fungi present in the room’s environment and in the stored components, we can draw conclusions regarding the risks of contamination in that part of the museum, in the rest of the collection, and to the health of staff and visitors (, 257–64). Among the great variety of fungi genera that are usually found in closed rooms, Penicillium and Alternaria stand out as significant allergens. Their pathogenicity may affect people who are immunocompromised, such as children, the elderly, and the immunosuppressed (). Among these fungus genera, certain species have a greater pathogenic potential than others, so it is important to continue the study until they are identified (, 5).

Safekeeping and conservation of artworks made with living matter, as is the case with the installation at hand, is a new situation for the Museo Blanes to address and research. The challenge does not end with the need to ensure the safekeeping, preservation, and accessibility of the work; additionally, it is necessary to ensure that conservation of the rest of the museum’s collection is not affected and that healthy conditions are maintained for staff and the public. It was confirmed that the components contaminated with living matter must be isolated, taking into account the intentions of the artist.

Conservation Strategies

Keeping microorganisms alive is a complex matter, both for conservation of the museum’s collection and for this particular work, as has been mentioned, due to the high risk of contamination to the rest of the collection and due to these particular microorganisms’ adverse effects on people. Considering the artist’s intentions, the museum ruled out applying biocide treatments and consequently made the choice to freeze the material containing living biological matter during periods of storage, and to isolate the installation during exhibition. The components of the installation containing living matter will be kept at a low temperature when in storage (likely somewhere between -10°C and -20°C) to prevent microbial development without the effects that a biocide would have on the microorganisms. When they are returned to favorable temperature and relative humidity, they will regain the ability to proliferate. As opposed to a standard procedure, and based on the conservation objectives established, there will be no packing protocol to minimize deterioration due to variations in humidity during these processes (). Only selected pages of the album will be interleaved with polyester film in order to avoid adhesion between pages, as the album is exhibited in an open position. Based on the same conservation objectives established, this interleaving will not be necessary to the conditioning inside of the binders, as they are exhibited closed. Each of the ten components will be individually packed in a hermetically sealed, double polyethylene bag and placed in containers with polypropylene inside a freezer at a temperature around -10°C.

The flash drive containing the audio and video was backed up in triplicate on the institution’s server and on two other external memory drives. It has been packed and put into storage under controlled environmental conditions (18°C to 20°C and 48 to 55 percent relative humidity). All digital material will be migrated to appropriate media every five years or sooner to avoid obsolescence.

The dirt that is on the desk will be the subject of future studies. Plans call for it to be stored at a low temperature, and its potential replacement will be considered. The remaining components of the installation will remain in Space F.

Proposal for Future Exhibition

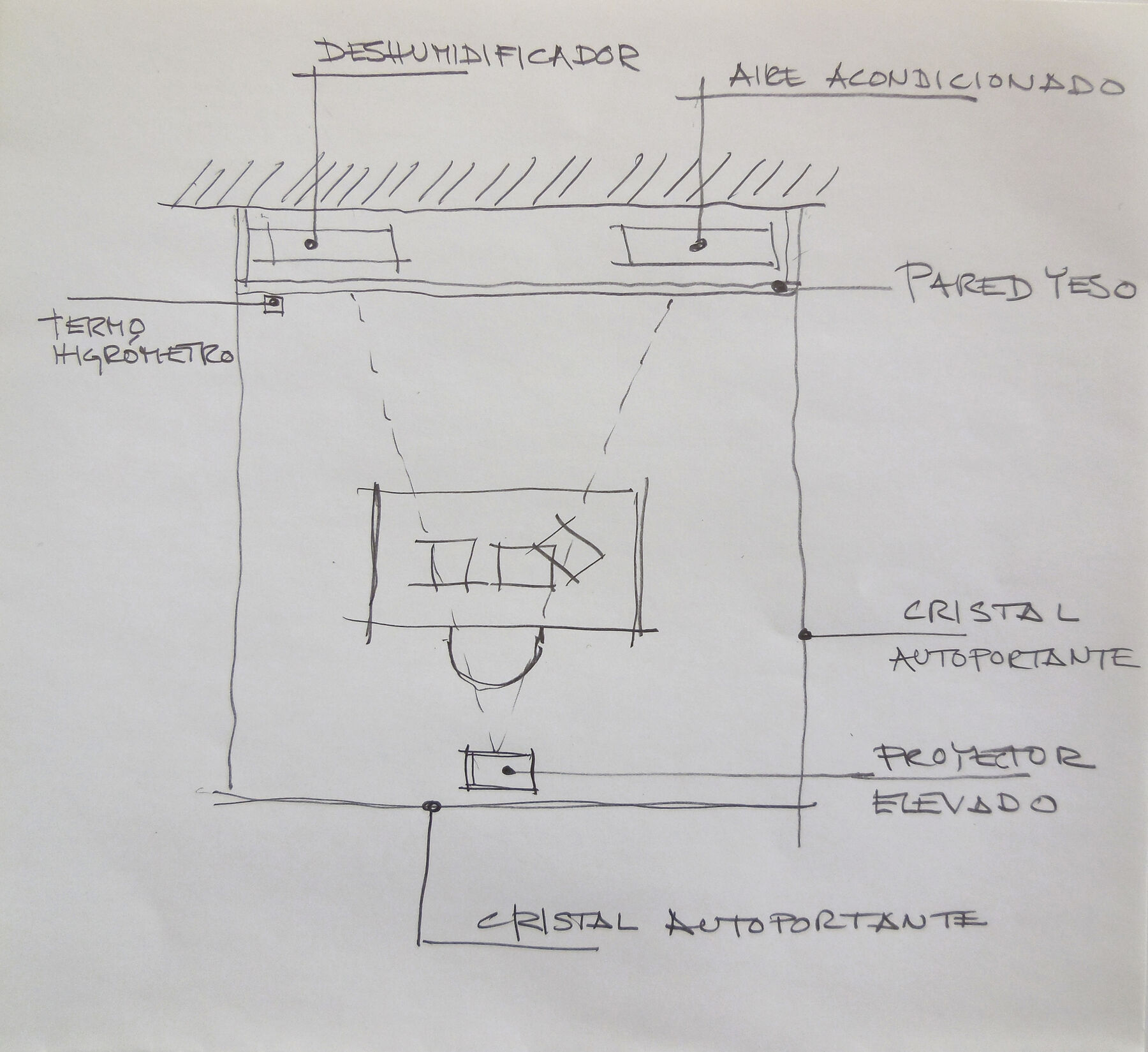

The proposal is to exhibit the installation inside an enclosure with side walls and a glass wall in front, a double back wall of white plaster with access for staff, and a lightweight roof. The size and type of lighting will depend on the curatorial proposal and the funds available for carrying it out. Inside will be a dehumidifier and an air-conditioning unit to maintain the appropriate environmental conditions to prevent possible condensation on the front glass wall. Ideally, the exhibition hall should have controlled conditioning of temperature and relative humidity. The video projector will be placed inside the enclosure, centered with respect to the desk, and the audio will play outside the enclosure, near the projector, following the instructions in the assembly protocol. A drawing of the proposal can be seen in fig. 14.10. The need to refresh and filter the air should be assessed ().

Final Considerations

This study of the conservation, storage, and exhibition of this installation revealed the importance of having the artist’s input and of conducting interdisciplinary research. The conducting of microbiological studies and exchange of criteria and experiences with different specialists exemplify collaboration among specialists, and were highly significant for the purpose of proposing and assessing new conservation strategies. Aspects such as the sustainability of these strategies continue to be subjects for debate concerning how to resolve the various situations we encounter in dealing with contemporary art.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their gratitude to the organizers of the Getty Conservation Institute symposium, MUAC and ENCRyM; visual artist Federico Arnaud; Nilda Mila of the Archive and Documentation Area of the Blanes Museum; Leire Escudero, Natalia Boero, and Marcos Delgado of the Blanes Museum Conservation Area; Daniel Sosa, director of the Photography Center of Montevideo; docents Fernando Osorio and Gisa Villanueva; and Rachel Rivenc for encouraging us to take part in this symposium.

Notes

Área de Documentación y Archivo, Museo Juan Manuel Blanes, admission of works, ST records, C5-CR-209/2018. ↩︎

Fernando Osorio Alarcón and Gisa Villanueva, Centro de Fotografía de Montevideo, Intendencia de Montevideo, Uruguay. ↩︎

Department of Biosciences, School of Chemistry, Universidad de la República, Uruguay. ↩︎

Claudia Barra, 2018 technical documentation, Área de Documentación y Archivo, Museo Juan Manuel Blanes, Informe de Conservación_Inv. 4085-18. ↩︎

Cristina Bausero, interview with Federico Arnaud, October 18, 2018, Área de Documentación y Archivo, Museo Juan Manuel Blanes. ↩︎

Federico Arnaud, “Protocolo de montaje e intenciones de conservación para la instalación: Lo que mata es la humedad,” 2019, Archivo del Museo Juan Manuel Blanes, Ingreso de obras; ST:C5-CR-209. ↩︎

Store F is an open area in the basement that is currently undergoing transformation into an isolated and equipped storage area. ↩︎

Water activity (a~w~) is the quantity of water available for growth of microorganisms. The term comes from food engineering and is determined as a ratio of pressures of water vapor. ↩︎

On BLAST see the US National Library of Medicine website: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST. ↩︎

Bibliography

- Al-Doory and Domson 1984

- Al-Doory, Y., and J. F. Domson. 1984. Mould Allergy. Philadelphia: Ed. Lea & Febiger.

- Álvarez 2017

- Álvarez, Raúl (Rulfo), ed. 2017. 48 Premio Montevideo de Artes Visuales 2017. Montevideo: Centro de Exposiciones SUBTE, Intendencia de Montevideo.

- Di Carlo et al. 2016

- Di Carlo, Enza, Rosa Chisesi, Giovanna Barresi, Salvatore Barbaro, Giovanna Lombardo, Valentina Rotolo, Mauro Sebastianelli, Giovanni Travagliato, and Franco Palla. 2016. “Fungi and Bacteria in Indoor Cultural Heritage Environments: Microbial-Related Risks for Artworks and Human Health.” Environment and Ecology Research 4 (5): 257–64.

- Frisvad and Samson 2004

- Frisvad, Jens C., and Robert A. Samson. 2004. “Polyphasic Taxonomy of Penicillium Subgenus Penicillium: A Guide to Identification of Food and Air-borne Terverticillate Penicillia and Their Mycotoxins.” Studies in Mycology 49:1–174.

- Pitt and Samson 2000

- Pitt, J. I., and R. A. Samson. 2000. Integration of Modern Taxonomic Methods for Penicillium and Aspergillus. Amsterdam: CRC Press.

- Samson et al. 1995

- Samson, R., F. Ribera, V. Sanchis, and R. Canela. 1995. Introduction to Food‑Borne Fungi. Baarn, the Netherlands: Central Bureau for Schimmel Cultures.

- Valentín, Muro, and Montero 2010

- Valentín, N., C. Muro, and J. Montero. 2010. “Métodos y técnicas para evaluar la calidad del aire en museos: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía,” edited by CARS – IIC Grupo Español, 63–81. Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía. https://www.museoreinasofia.es/sites/default/files/actividades/programas/metodos_y_tecnicas_restauracion.pdf.

- Valentin 2010

- Valentin, Nieves. 2010. “Microorganisms in Museum Collections.” Coalition, no. 19 (January): 2–5. http://www.rtphc.csic.es/issues/19_01.pdf.

- Voellinger and Wagner 2009

- Voellinger, T., and S. Wagner. 2009. “Cold Storage for Photograph Collections: Vapor-Proof Packaging.” Conserve O Gram, nos. 14/12: 2–5.