24. Dissolving Matter: Notes on Símbolo descarnado

- Darío Meléndez

Thus formless is not only an adjective having a given meaning, but a term that serves to bring things down in the world, generally requiring that each thing have its form. What it designates has no rights in any sense and gets itself squashed everywhere, like a spider or an earthworm. In fact, for academic men to be happy, the universe would have to take shape. All of philosophy has no other goal: it is a matter of giving a frock coat to what is, a mathematical frock coat. On the other hand, affirming that the universe resembles nothing and is only formless amounts to saying that the universe is something like a spider or spit.

—Georges Bataille, The Sacred Conspiracy, 1936

Why am I interested in working with organic matter? Not intending to provide a definitive answer, I could point out that my initial training as a traditional painter in the studio of artist Luis Nishizawa awoke in me a taste for process and for the emanative nature of materials undergoing transformation, which soon led me to become disenchanted with the fixed image that takes shape within a pictorial object. Even in those days, I had an irrepressible impulse for the uncertain and the vague, for all those intermediate phases in the construction of a painting in which the image would appear to be forming and/or disappearing. Drawings superimposed, glazes that melt the underlying layers, and varnish drippings were some of the visual experiences that led me to fall in love with unstable materials. What was behind that impulse? I could start by saying that maybe those evolving materials reverberate with what I am seeing, experiencing, and breathing in Mexico, and in Mexico City in particular. The stench of death is nothing more than the scent of change.

The Work

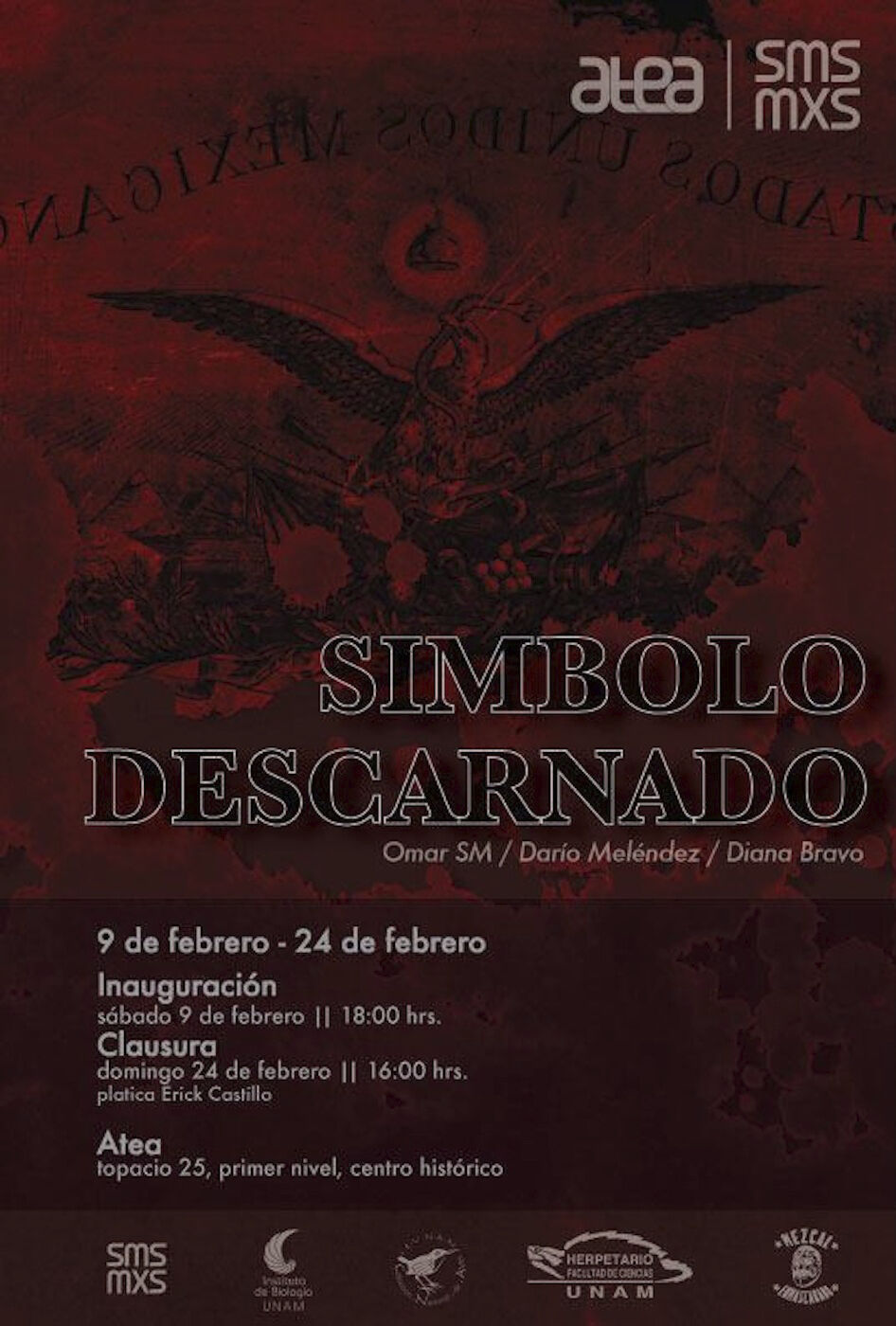

Símbolo descarnado was a collective installation exhibited from February 9 to 24, 2013, at ATEA in Mexico City (fig. 24.1).1 It consisted of an ephemeral mural of the national coat of arms, drawn with cochineal by Omar Soto; a sound spatialization by Diana Bravo based on amplified noises made by larvae; and the rotting carcasses of an eagle and a serpent inside a glass case, created by me, Darío Meléndez. The main intent was to present, in the white cube, the atmosphere of deterioration in which my country is submerged and to question the viewer through an experience of formlessness in contrast to the asepsis of the site. The strategy for delivering criticism of the eroding structure and validity of the Mexican state—symbolized by the eagle and serpent on the nation’s coat of arms—was to utilize the aesthetic, performative, and sonic possibilities of material and symbolic corruption through different approaches.

In Soto’s ephemeral work, the corruption consisted of those attending the opening using their hands to erase (redraw?) a mural based on a nineteenth-century lithograph of Mexico’s national coat of arms (fig. 24.2, fig. 24.3, fig. 24.4). In this way, the death of the state, present in its own foundational image, was deformed by the viewers themselves. In addition, because the mural had been made with cochineal, a reddish organic colorant with a heavy historical weight, the hands that blurred the image came away stained, evoking a criminal complicity. Instead of existing only as an intellectual dialogue with the viewer, this drawing sought to involve the bodies of the attending public. Having a collective participate in this piece demonstrated that the ideals of our nation were devoured when they took the form of institutions and political figures.

Figure 24.2

Figure 24.2AU: Call out for fig. 24.4 missing; please indicate where it should be placed.

Bravo’s sound spatialization consisted of an audio system that amplified the tiny sounds of insect larvae devouring rotting meat. Despite the morbid concept, the sound, instead of being terrifying, was almost a white noise, somewhat aquatic, evoking oceanic movement. Bravo revealed death as a subtle process of disappearance, disassociated from the horrible, abject images provided by our daily imaginary. Also, the sound was not continuous, but would gradually crescendo, filling the space little by little. Initially almost imperceptible, the insects’ hushed chewing would rise in volume to become the opaque roar of the night sea of which we are perhaps a part.

This treatment of sound, unnoticeable at first, took me back to a literary reference from the early years of my education: the poem “A Carcass” by Charles Baudelaire:

My love, do you recall the object which we saw,

That fair, sweet, summer morn!

At a turn in the path a foul carcass

On a gravel strewn bed,The blowflies were buzzing round that putrid belly,

From which came forth black battalions

Of maggots, which oozed out like a heavy liquid

All along those living tatters.And this world gave forth singular music,

Like running water or the wind,

Or the grain that winnowers with a rhythmic motion

Shake in their winnowing baskets.2

As can be seen in the foregoing sonorous lines, the resonances between readings, media, and authors seem to address the reappearance of the forms of ancient art in times subsequent to those described by Aby Warburg (, 20). I would like to point out that in this case it is not so much the reappearance of the form itself; that is, it is not a simple replica, but more like making the energy emerge from the present. Thus the importance of the act, of the presence of the matter itself in its contingency.

The last part of the installation was a partially sealed glass case containing the carcasses of an eagle and a serpent in suspension, like a monstrous apparition (fig. 24.5, fig. 24.6, fig. 24.7, fig. 24.8, fig. 24.9). Both were rotting, and they were clearly alluding to the nation’s coat of arms. As in the other cases, corruption of the symbol was the essential agent of the piece, but in this case the deterioration was real. In counterpoint to the idea of representation in the recording and amplification of the sound of the larvae in Bravo’s contribution, and in the participatory drawing and erasing of Soto’s mural, this part included the presence of the actual symbol in and of itself deteriorating. This situation gave the installation greater corporeality—and another unforeseen factor that enriched the initial idea, namely the smell of death. Thus, the intention of evoking the atmosphere of corruption of the site from which the piece was submitted, Mexico City, appeared to be complete.

Figure 24.5

Figure 24.5In the words of the art critic Sandra Sánchez, what the piece reveals to us is that there can be life even in the midst of destruction (). In the aquatic sounds and the red stains throbbing on the wall, in the fly larvae, and in the beetles issuing from the carcasses, we find the prelude to a new beginning. Decomposition is merely a journey toward another place. From this angle, the whole could be read as a rite of farewell, a return to the earth with a view toward transformation, or an elevation of the spirit (of the ideal in this case).

The latter idea, which speaks of a connection between decomposition and the spiritual world, has already been addressed by the twentieth-century alchemist Fulcanelli when he mentions the works of José Mateo Orfila and Marie-Guillaume-Alphonse Devergie, nineteenth-century French physicians who conducted experiments on the slow, gradual decomposition of human cadavers:

The odor gradually diminishes, eventually reaching a stage where all the soft parts scattered on the ground are nothing but a blackish, muddy debris, with a somewhat aromatic smell. As for the change from stench to scent, one must observe its striking similarity with what Old Masters said about the Great Work of Physics, two of them in particular, Morienus and Ramon Llull, who state that the foul smell [odor teter] of the dark decay is followed by the sweetest scent, because it is the scent of life itself and heat [quia et vitae proprius est et caloris]. (, 11)

Final Notes

First, I believe that although the emotive, formal, and acoustic presence of the installation was powerful, it was circumscribed within the innocuous circle of emerging contemporary art. Originally presented at ATEA, a space that is part gallery, part workshop, and part cultural company, the work was contained, not only in terms of its visibility, but also in terms of its capacity to influence our daily imaginary. This last thought is due to the political implications of the work. If the piece were really to be ferocious, it should have been shown in a public space, without the aid of the sanctifier (here I am referring to the sacred in its most domesticated sense) of the white cube. Leaving the piece with no other defense than its own corporeality and seeing how it would be exploited, erased, or ignored in real life is the most desirable treatment for this type of proposal. Truly caustic criticism is done in the open air.

In addition, the presence of the decayed matter, even placed in this sociopolitical expression, implores us as well, as bodies undergoing decay. On viewing its slow, fascinating fall, we seem to return to a sense of mortality and fragility, as in the words of Radiohead’s song “Fake Plastic Trees”: “But gravity always wins.”3

Notes

Arte Taller Estudio Arquitectura (ATEA, or Art Architecture Study Workshop) is a cultural center founded in 2010 devoted to promoting dialogue between different disciplines. This building, located on Calle Topacio, Mexico City, holds the multidisciplinary collective Somosmexas, founded in 2006 and consisting of ten young artists. These artists promote art exhibitions, workshops, and projects with institutions both on site and externally. They also link art to the surrounding context: the heart of the La Merced neighborhood (). ↩︎

, 163–65. ↩︎

Radiohead, “Fake Plastic Trees,” from the 1995 album The Bends. Watch the video on YouTube: https://youtu.be/n5h0qHwNrHk. ↩︎

Bibliography

- Baudelaire 2005

- Baudelaire, Charles. 2005. Las flores del mal. Madrid: Cátedra.

- Fulcanelli 1974

- Fulcanelli. 1974. El misterio de las catedrales. Buenos Aires: Editorial rotativa.

- Sánchez 2013

- Sánchez, Sandra. 2013. “La historia no existe (cuatro artistas bordeando los hechos).” GASTV, n.d., https://gastv.mx/la-historia-no-existe/.

- Valdivia 2017

- Valdivia, Mónica. 2017. “ATEA: Renovación cultural en la Merced.” NEXOS, April 10, 2017, https://cultura.nexos.com.mx/?p=12524.

- Warburg 2005

- Warburg, Aby. 2005. El renacimiento del paganismo: Aportaciones a la historia cultural del Renacimiento europeo. Madrid: Alianza.