2. Can We Use the Concept of Programmed Obsolescence to Identify and Resolve Conservation Issues on Eat Art Installations?

- Claudia María Coronado García

Daniel Spoerri and a few other artists, including Dieter Roth and Peter Kubelka, decided in 1970 to organize an exhibition featuring quite a few experiments they had carried out since 1968, when Spoerri Restaurant opened, and then subsequently the Eat Art Gallery, which was unique in its presentation of something as common as food as capable of inducing emotions, memories, and sensations, even evoking personal memories among visitors. The show was titled Eating the Universe and took place at Burgplatz in Düsseldorf, Germany. Spoerri described it as follows:

a) the tables in the restaurant became trap-paintings, b) as in my “grocery shop” regular foods (meals) are exhibited as artworks, c) the works of art are in transformation (and transient), . . . d) everyone could have produced at will his own trap-painting under my license, and e) the sense of taste was directly involved, in addition to touch and sight, etc. (, 159)

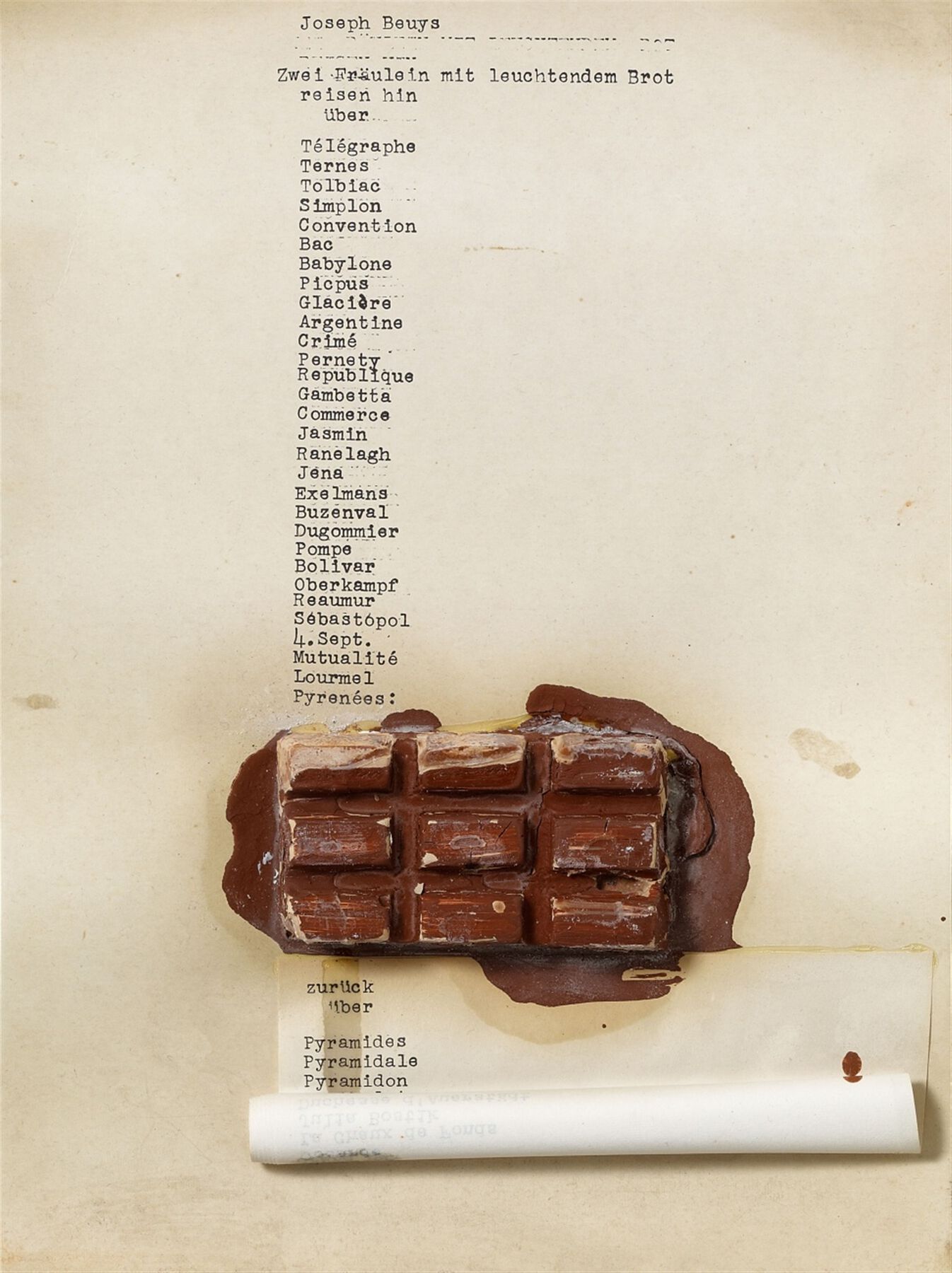

These artistic principles were the foundation of Eat Art. The artists intended to demonstrate the power of food—that it can communicate meanings, transmit clear ideas, and provoke even the most passive observer. The exhibition evidenced that using food as a material for artistic expression is just as or even more powerful than re-creating it on canvas. The name Eat Art is now commonly used for installations containing some element that is edible or closely linked to food—so much so that some previous artworks by Roth or Joseph Beuys that were not created with the intention of eating the food are now considered Eat Art installations (fig. 2.1).

Figure 2.1

Figure 2.1This paper discusses Eat Art installations and proposes the concept of planned obsolescence to approach their conservation. What would that obsolescence look like, and how would we recognize it?

Typologies of Eat Art Installations

Little is firmly established about the conservation of Eat Art, and even less about how to determine when changes to the organic parts are decay intended by the artist versus decomposition that should be combated. Yet other installations involve a constant replenishment or replacement of materials to function as intended.

In the history of art, food has often been portrayed, in one form or another, as a symbol of power and well-being. It is thanks to Spoerri, however, that the art world came to consider food items as raw material able to “generate associations that, together with the forms into which they are shaped, establish the subject or content of the work of art” (, 13). Food items in Eat Art installations can fulfill a variety of functions. Using food promotes a fuller sensory experience, inviting us to utilize not just our vision, but also our sense of smell, and even maybe touch and taste. Involving more than a single sense makes the created experience stronger. The artists have achieved their objective if they generate in the viewer whatever sense of playfulness, cryptic-ness, grotesquerie, eroticism, repulsion, savageness, transgression, or surreality that they intended. The material creates a visual or sensory experience in a specific environment (fig. 2.2).

Figure 2.2

Figure 2.2Food items in Eat Art installations might suggest the fleetingness of life because, just like us, the food will undergo change that is inherent to its organic state. The work will start out with one shape, color, and smell and undergo transformations until these aspects are unrecognizable. Perhaps the piece will completely deteriorate. This deterioration is a clear reminder of our fragile nature, of the organic decomposition that every human being is destined to undergo. As Pere Salabert puts it, from the beginning our bodies contain an anomaly, an error in the production process. Art that advocates decomposition of matter is connecting us with our body’s final destiny. It forces us to confront what we strive to avoid: “the expiration of living matter, its stinking vocation, its propensity to decay,” because materials that must be eaten will degrade, decompose, or even perish, which is what will convey meaning or transform into the sensations and interactions between ourselves and the works of art (, 86). This is sometimes confusing because these installations promote consumption, asking for direct interaction rather than being simply observed; they are presented as a temptation that breaks with traditional exhibition rules by asking us to approach the artworks, touch them, even eat them.

The wide variety of food that has been used as art material has led to a great diversity in the types of artworks created, as well as in terms of the time and place of exhibition, the idea to be conveyed, and the type of audience the work is intended to impact. This variety of presentations and contexts means that works that might look alike could require different actions from their audiences and have different meanings. In other words, not all artists endow the same food with the same meaning or significance; the food might fulfill very different functions. New artworks employing food items are still able to produce new and different discourses, and new sensations and experiences (fig. 2.3).

Figure 2.3

Figure 2.3At present, there is no single way to characterize these types of installation. They could be categorized by era, by artist, by type of material, or by the artist’s intention. Intentionality encompasses everything from the reason why the artist selected, from among various materials, some in particular and assigned to them specific tasks to perform within an exhibition space to the way in which they will interrelate with visitors. This categorization is based on prior knowledge of the installations; they cannot be grouped by the type of food chosen because, as we will see, three installations using chocolate as the raw material could have quite different intentions behind them (). Knowing the ideas behind the choice, and familiarity with the artist’s previous work, enables an understanding of what motivated the artist to select that material and its significance within the particular context. With food installations, at least three typologies of intentionality can be recognized.

The first group comprises edible art objects that the artist has endowed with an emotional charge, sensitive to human relationships with this type of food item. This group, which conveys sensations and reactions, utilizes the physical, formal, and material qualities of the food products to create a connection with viewers. These objects are sometimes treated chemically so they will not change over the course of the exhibition in which they will be presented, as is the case depicted in figure 2.2, where in 1992 Sandy Skoglund stabilized Cheez Doodles chemically to keep their peculiar color and form.

Another typology reflects on the daily ritual of eating, tasting food in communion, which brings families together around the table not only to eat but also to share how their day has gone, listen to one another, and strengthen emotional ties. This typology attempts to create moments in which humans, through food, share experiences and communicate with others while simultaneously satisfying their own biological and social needs.

The third situation consists of exhibitions in which the artist allows the process of deterioration to be a fundamental part of the experience. The objects displayed will not only communicate with the visitor through their sense of vision; smell will likely play an important role as well. These foods have a limited shelf life if they are not consumed, but in art their usefulness is extended through decomposition.

Each of these typologies corresponds to the action or the function that the artist wants the food to fulfill, and each of them asks the audience for a specific (re)action that reinforces the intention behind the choice. Consequently, any one of these works presents a challenge to the viewer—and to the conservator—through smell, vision, presentation, and the actions taking place around them.

Case Studies

To put forward just one example, a great number of artworks use chocolate as a raw material. Three case studies are discussed here, each representing one of the typologies described above: Sonja Alhäuser’s Braunes Bad V (Brown Bath V, 2009/2015, fig. 2.4), Laurent Moriceau’s Found and Lost #1 (2003, fig. 2.5), and Janine Antoni’s Lick and Lather (1993, fig. 2.6). All three are made with edible milk chocolate. All three are portraits of the artists. But they differ by period, size, and above all function.

Figure 2.4

Figure 2.4 Figure 2.5

Figure 2.5 Figure 2.6

Figure 2.6Alhäuser exemplifies the first typology described above. Her work promotes the culture of communion and often involves sculptures and installations made with different edible items, including chocolate, to smell, taste, feel, and eat. Many of Alhäuser’s works not only promise pleasure in the traditional sense but also provide the taste buds with a direct, immediate pleasure (). Braunes Bad V takes the viewer by surprise. Nothing suggests opulence more than those banquets where one sees a fountain of endless chocolate for dipping fruit. This work is a fantasy brought to life, the dream of any chocolate addict, from the smell upon entering, to the possibility of tasting it as part of the experience that Alhäuser promotes.

Found and Lost #1 portrays Moriceau himself in three different mediums: bars of soap, lollipops, and a life-size version in chocolate. At first, the project seems to be a set of self-portraits. But each one of these propositions creates multiple dialogues, a set of approaches that address not only the relationships between audience and artist and between audience and artwork, but also the artist’s sensual approach to the body of the viewer (). Each one presents a “communion” of the artist’s body with visitors. Moriceau as executioner smiles as he distributes and redistributes his body, sacrificing himself, one might say, so others may taste. Here audience participation—not only as observers but also as “cannibals”—is necessary for the work to make sense.

Antoni’s Lick and Lather began with a mold of the artist’s own head that was used to cast seven iterations with soap and seven with chocolate. These self-portrait busts observe us in a challenging manner, like bishops on a chessboard, but we cannot eat them or touch them; we can only observe them and witness their transformation over the years. Antoni uses the soap bust to wash her body, and she licks the surface of the chocolate bust with each encounter. She has specifically prohibited these actions from being undertaken by anyone but her.

What these examples demonstrate is that, although they might appear similar in form and rendered in a common material, each artist expects the public to react and interact in a specific and different way. So, as the conservator, how does one know what to do? In which cases is it valid to conserve the works, and in which cases not? In which cases should they be allowed to deteriorate and in which cases should they be remade, changed, or replaced so they will continue to fulfill their assigned function?

Based on the foregoing typologies, the next step would be to assess what percentage of the work is composed of organic matter and what one is expected to do with it. Only when work is meant to be observed—the organic matter is the work itself and cannot be replaced in the event of deterioration—must the work be conserved through preventive measures, perhaps by storage in a climate-controlled room or case. Or, if the artist so agrees, it can be intervened in with materials appropriate for its preservation.

In the other two cases (consumption or replacement) the organic materials present are expected to fulfill a specific task within the exhibition. In other words, if the work is made to be eaten, then the museum or gallery will allow it to be consumed. In the case of Moriceau, the work was produced for the opening of an exhibition, and once distributed, there would be nothing left of it, only a record of the action and the experiences of the visitors. The work will not be repeated until the artist decides to do so.

There are several ways to resolve the matter of replacement. It can be when the artist is planning a new exhibition, or it might be periodic and/or continual. When replacing organic materials, questions arise as to the appropriate person to do so, how it should be done, when should it be done, and why should it be done. It should not be done if these questions have not been answered or if one lacks a deep knowledge of the artist’s intention and the various meanings of the work.

Programmed Obsolescence

Material replacement can be a systematic modification regulated by the artist, who dictates the intervals for replacement, its parameters, and the reasons for doing so. In some cases, the system or protocol to be followed confirms that replacement should be continual; otherwise, the installation will cease to function. Merriam-Webster defines obsolescence as the process of becoming obsolete or the condition of being nearly obsolete. Therefore, we are dealing not only with obsolescence, but also with programmed obsolescence, as in, “a business strategy in which obsolescence (the process of becoming obsolete, that is, no longer fashionable or no longer usable) of a product is planned and built into it from its conception” ().

The concept of programmed obsolescence arose in 1920, when businesspeople from different light bulb manufacturers decided to regulate the characteristics of a commercial light bulb: its electrical resistance, materials, and life span. At the time, it was normal for light bulbs to last for fifteen hundred to two thousand hours. But the Phoebus cartel, as it would afterward be called, determined that it would be more profitable for the light bulb market if they did not last that long, and the limit was newly set at one thousand hours. Even today there are regulations around how many hours a light bulb should function.

There are many reasons why an object can become obsolete, even several ways of classifying it. John Ippolito and Richard Rinehart () state that technology, institutions, and legislation can be the causes of producing obsolescence, referring to new media and social artworks. Another classification system, based on economic processes, can depend on an item’s quality (because it has defects or a malfunction), on desire (new styles or fashion on the market), or on the item’s function if it is no longer useful and needs to be replaced. We will focus on this last classification: programmed obsolescence based on function.

Joseph Beuys’s Capri Battery (1985, fig. 2.7), a light bulb with a plug socket and a lemon, summons the bright Mediterranean sun, and relates to the artist’s interests in energy, warmth, and the environment. This artwork is peculiar for several reasons. Beuys required that when it is exhibited, the lemons may come only from the island of Capri, Italy, because he felt they are the best, and because they could fulfill the essential requirement of form and function in an exhibition of one thousand hours. With each presentation, a new lemon is procured so the work will function properly. The citric acid in the lemon contains an electrolyte that can conduct electricity, such that it is essentially an electrochemical battery. Once a thousand hours have elapsed, the lemon ceases to fulfill the function that was assigned to it and needs to be replaced, which is clearly comparable with the previously defined concept of programmed obsolescence.

Figure 2.7

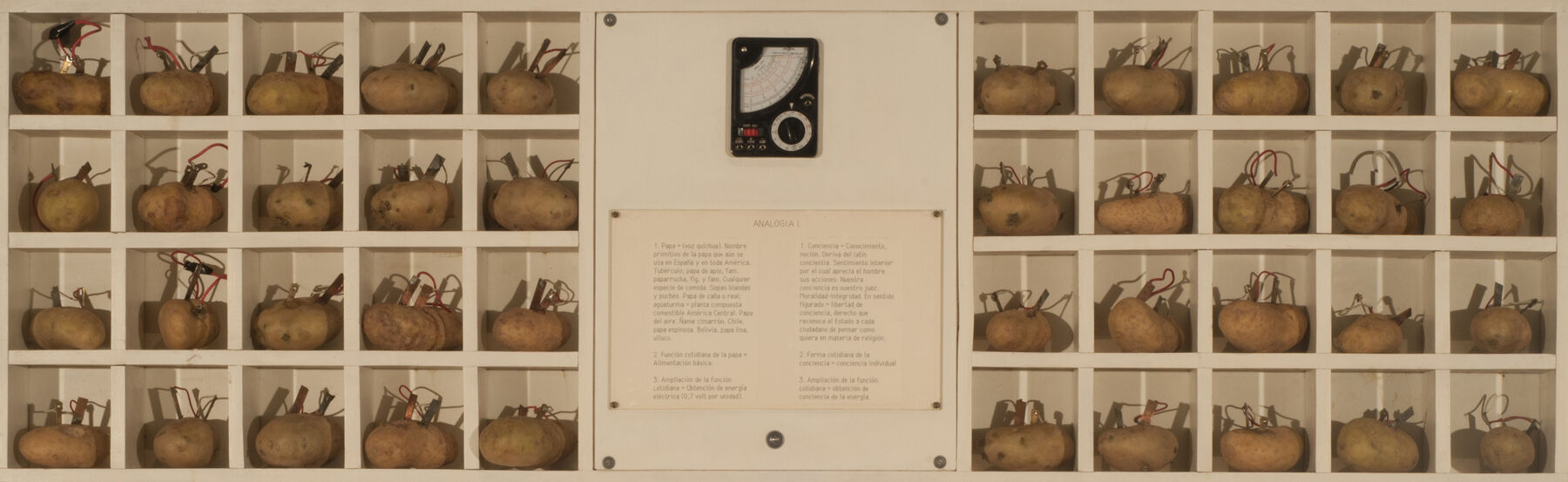

Figure 2.7A similar case is the work of Víctor Grippo, an Argentinian artist who, in the 1970s, created a series of works that deal in traditionally opposing binaries such as art versus science, nature versus culture, and real versus artificial, such that they evidence the basic processes of cooperation, production, and consumption and reflect on the city-versus-country duality. The works are related to conceptual art and utilize organic materials such as potatoes and bread. His best-known works from that period are Analogía I (Analogy I, 1970–71, fig. 2.8), Analogía IV (1972), Algunos oficios (Some Jobs or Some Trades, 1976), Valijita de panadero (Small Bread Maker’s Suitcase, 1977), and Tabla (Table, 1978) (). In these artworks, a voltmeter makes evident that potatoes carry energy. What is interesting about these installations is that their organic components must be replaced when the energy is exhausted. That is, the potatoes as batteries must be replaced by others with similar characteristics every so often for the artwork to continue to function.

Figure 2.8

Figure 2.8Giovanni Anselmo’s Untitled (Sculpture That Eats) (1968) is also a work of this type. In this case, it is essential to change the romaine lettuce leaf on the granite monolith about every week, before it rots or dries up, because the artistic intent is to suggest that this sculpture needs food to exist.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s candy works are another example where understanding the reasons behind the artist’s rules for how the work should exist and function is key. This may permit us to identify in them a few elements related to programmed obsolescence, since there are certain preestablished guidelines, such as the type of candy to be used in “Untitled” (A Corner of Baci) (1990). The work—an accumulation of Baci Perugina chocolates, which have a specific shiny wrapping—converts a pile of chocolates into a recognized work attributed to this author. Visitors to the museum or gallery are invited to take away a candy and eat it later. The weight, disposition, location, and replenishment rate of the pile of candies may vary as an exhibition progresses, but only within certain set parameters. The candy works of Gonzalez-Torres have some aspects that must always be the same, but also various malleable aspects whose performativity, if you will, makes them unique and unrepeatable. We must be careful, since previous research as well as the intention of the artist are fundamental to understanding when, how, and in what way the concept of programmed obsolescence plays into decisions on the conservation and restoration of a particular work.

Conclusions

The concept of programmed obsolescence is present in some Eat Art installations, and understanding it facilitates the conservation approach to take. We must recognize when the artist has the intention of replacing edible material for the artwork to function, versus when the artist desires the deterioration or other transformation of the materials.

In the case of installations in which the artist has the intention of replacing edible material for the artwork to function, it should be understood that the ephemeral elements are the guiding principle and that, without systematic replacement, the work will no longer exist as intended. But replacement or substitution must take into account the considerations specified or suggested by the artist so that the modifications do not alter the meaning or diminish the work’s ability to fulfill the artist’s intention.

These kinds of installations question the role of the conservator and call for study toward a full comprehension of their intentions and meanings. The concept of programmed obsolescence may be inherent in them, so understanding if their function is affected by the deterioration of the edible materials will help us prevent the installations from actually becoming obsolete.

Bibliography

- Buskirk 2003

- Buskirk, Martha. 2003. The Contingent Object of Contemporary Art. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Hummelen 1999

- Hummelen, IJsbrand. 1999. “Decision-Making Model for the Conservation and Restoration of Modern Art.” In Modern Art: Who Cares? An Interdisciplinary Research Project and an International Symposium on the Conservation of Modern and Contemporary Art, edited by IJsbrand Hummelen, Dionne Sillé, and Marjan Zijlmans, 4–18. Amsterdam: Foundation for the Conservation of Modern Art.

- Ippolito and Rinehart 2014

- Ippolito, John, and Richard Rinehart. 2014. Re-collection: Art, New Media, and Social Memory. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- MALBA 2012

- MALBA. 2012. “Víctor Grippo: Homenaje.” https://malba.org.ar/evento/victor-grippo-homenaje/.

- Novero 2010

- Novero, Cecilia. 2010. Antidiets of the Avant-Garde: From Futurist Cooking to Eat Art. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Salabert 2004

- Salabert, Pere. 2004. La redención de la carne, hastío del alma y elogio de la pudrición. Murcia, Spain: Editorial Centro de Documentación y Estudios Avanzados del Arte Contemporáneo (CENDEAC).

- Schultz n.d.

- Schultz, Michael. n.d. “Sonja Alhäuser.” https://www.schultzberlin.com/de/sonja-alh%C3%A4user.

- Taddei 2009

- Taddei, Jean-François. 2009. Les Perméables = The Permeables. Paris: MeMo.

- The Economist 2009

- The Economist. 2009. “Planned Obsolescence.” March 23, 2009. https://www.economist.com/news/2009/03/23/planned-obsolescence.