4. The Eternal Metabolic Network: Fluxus, Food, and Ecofeminism

- Natilee Harren

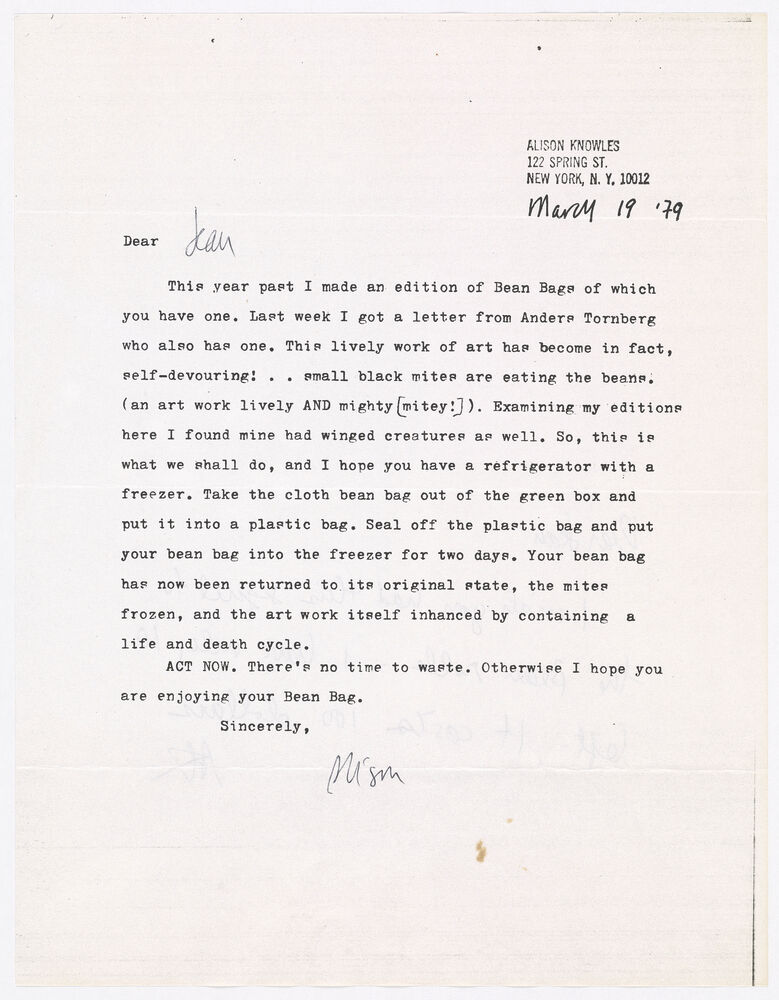

In 1978 Fluxus artist Alison Knowles (b. 1933) assembled the boxed edition Bean Bag, one among numerous works she has created involving a favorite food material, dried beans (fig. 4.1). Not long after, the small collection of legumes and related ephemera unexpectedly became the object of nonhuman consumption by attracting mites, leading the artist to send notes to collectors instructing them to place the work’s bean-filled cloth bag in a freezer for two days in order to exterminate the insects. Knowles’s charming letter argues that the infestation effectively enhances the work of art, now made “lively,” “self-devouring,” and “mighty” (pun intended) by having incorporated “a life and death cycle” into its materials and process of creation (fig. 4.2). Seen through this episode, Bean Bag instructively orients us to the international Fluxus collective’s other, more ephemeral engagements with food, such as curated feasts, collaborative cooking experiments, and interactive and edible multiples. Food was embraced as an artistic material by many Fluxus affiliates, including George Maciunas, Benjamin Patterson, Takako Saito, Daniel Spoerri, Ben Vautier, and Robert Watts, with the full knowledge that it degrades, decays, and disappears as it is consumed by those who eat it or simply by time and the elements ().

Figure 4.1

Figure 4.1 Figure 4.2

Figure 4.2Linking the disciplines of contemporary art history and conservation, this essay speculatively explores how Fluxus artworks generate an “eternal metabolic network” in which conservators and curators are enlisted in a program of permanent creation alongside and in the wake of the artist.1 Following from the pioneering work of Knowles and connecting it with discourses of ecofeminism and the Anthropocene, one can draw an art historical vector to contemporary art practices involving food and other biological materials as poignant means of addressing humans’ caring relationships to the environment, its objects, and one another. Such works engage an eternal metabolic network of nonhuman “living matter” in ways that do not shy away from its inevitable transformation. The ever-unfolding chemical processes that ostensibly degrade the artwork as a static object in fact sustain organic life, thus enriching the artwork’s conceptual value while enlisting a shifting array of collaborators in its ongoing care.

Adopting food as an artistic material was a direct means for Fluxus artists to approach their avant-garde goal of merging art with everyday life on the way to making art—or at least its qualities of preciousness and elitism—obsolete. In 1974 the Lithuanian American Fluxus artist George Maciunas, a leading organizer of the collective, gathered together all the empty packages from food items he had consumed over the past year and called it an artwork. The assemblage, One Year (1973–74), is now part of the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. According to Maciunas, the arranged towers of (now depleted) industrially processed consumer packaged goods—everything from rice pilaf and granola to cottage cheese, preserved strawberries, and instant dry milk—were deserving of aesthetic appreciation. Indeed, One Year is an impressive readymade in the post-Duchampian tradition, while its homage to everyday commercial design aligns with the aesthetic orientation of Pop. But One Year gestures beyond those immediately visible art historical affinities. As David Joselit has argued, food was for Fluxus artists the perfect “metabolic readymade” or “bio-readymade.” A (nearly) universally accessible and approachable material able to, in Joselit’s words, “articulate the metabolism of life with the global circulation of commodities,” Fluxus food objects cannily addressed the symbolic social body by passing through the actual body of the individual. “It was precisely by linking individual bodies—what might be called wetware—to the hardware of global markets that Maciunas opened an aesthetic paradigm in which organic flux was metabolized as art—as Fluxus” (, 192, 196, 192).

Indeed, Fluxus art provides a theoretical object lesson in how to manage and bear material indeterminacy of all kinds, particularly in matters of curation and conservation (). This was brought home to me through my encounter in 2009 with Benjamin Patterson’s Hooked (1980, see fig. 11.8 in this volume) in the Jean Brown papers of the Getty Research Institute. Hooked is a readymade consumer-grade fishing tackle box filled with dozens of small objects outfitted with hooks, all of them joke lures assembled by the artist. It also contains a can of sardines in tomato sauce—sustenance for the unlucky fisherman—which had corroded to the point of leaking when I called it up from storage during my research, unwittingly releasing its putrid stench throughout the GRI special collections reading room. Quite literally in this case, organic flux had been metabolized as art. With advice from Patterson and GRI chief curator Marcia Reed, objects conservator Albrecht Gumlich devised a conservation solution that entailed carefully documenting the old can and adding in its stead a new reference can that had been emptied, sanitized, and refilled with a weight of plaster equivalent to its prior contents (). Taken alone, neither the old (exploded, degraded) can, now represented by a printed image, nor the new (imposter) can, with its false contents, constitute a total solution. Only taken together do the cans adequately convey the material truth of the original object.

The provisionality of this solution—much enjoyed by the artist, who called it “Montazuma’s [sic] revenge” on the museum—is philosophically rooted in Fluxus artists’ general attitude and approach to objects, which draws on cultures of performance.2 Foundational to historic Fluxus practice in the 1960s and 1970s was the format of the event score, typically a brief text written in colloquial language instructing the reader to make a gesture, object, or observation within their immediate environment. Centering their practice on scores composed to be interpreted by diverse performers and makers, Fluxus artists were groundbreaking in translating performance protocols into collaboratively produced, highly interactive art objects (). Accordingly, Fluxus output stands in an ever-curious relationship to institutions and disciplines, existing between art history, poetry, music, dance, and performance studies; between the unique object and the edition or multiple; and between the art museum’s permanent collection and other special collections, libraries, and concert halls, as well as the public domain. Ephemerality and iterativity are fundamental to the ontology of the Fluxus work. At the same time, the score as a technology of performance inscription and reanimation carries with it a long history and culture of preserving artistic intent. Fluxus artworks produce an eternally evolving system that toggles between abstract instructions (scores, notations) and substantive materials (often ephemeral, unstable, biological), necessitating a rethinking of conventional approaches to conservation in order to better honor and even embrace their essential qualities of change (; ).

Fluxus offers ethical case studies and useful models for curators and conservators thinking through a broad array of subsequent contemporary art practices wherein the preservation of an aesthetic concept requires de-privileging specific original materials and embracing processes of transformation and even decay. The putrefying elements of Patterson’s Hooked present an extreme conservation problem, one seemingly opposite the conceptual, text-based, more readily enduring format of the Fluxus event score. Indeed, Fluxus scores have received scholarly attention for modeling an artwork that lives on precisely because of its acceptance of change through varying interpretations, thereby de-fetishizing the work of art as a unique, original, authentic, materially fixed entity. In comparison, the collective’s provisional food objects present a complementary tactic, albeit in more material terms. As Joselit writes, “Fluxus stages an art of witnessing: It testifies to the thin line between organic stuff (i.e., food) and human consciousness and sociality, and it marks the fragile border between life and its expiration as shit” (, 200). By reminding us that all works of art are to some degree transitory, Fluxus engagements with food orient our attention to the ongoing, collaborative labor of caregiving that artworks engender.

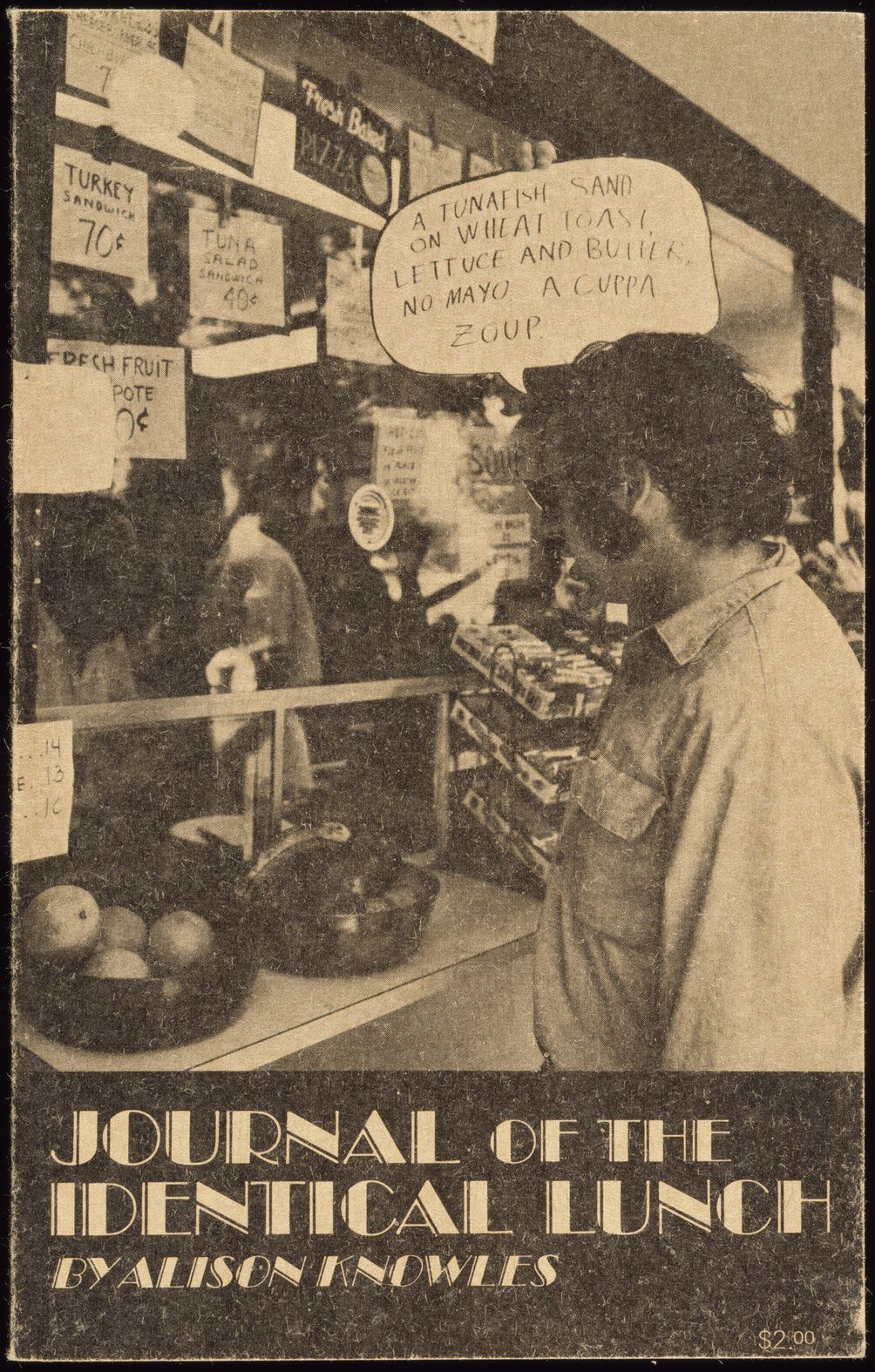

In addition to calling to mind global commodity networks, as Joselit posits, Fluxus work with food illuminates the intersections of feminist and environmentalist concerns. Among Fluxus artists, Knowles’s elevation of everyday objects and gestures, including domestic and caregiving activities related to food, was especially successful in trans-valuing the minor into something precious and worth honoring through care (; ). Her score Proposition #2 (Make a Salad) (1962, fig. 4.3) instructs the performer, quite simply, to “make a salad.” And The Identical Lunch (1969) reframed her habitual midday meal as a readymade event for others to perform (as maker and/or eater): a tuna fish sandwich on wheat toast with lettuce and butter (no mayonnaise) and a large glass of buttermilk or a cup of soup. Among a multitude of works involving the cheap and lowly bean, Knowles published the editioned Fluxus object Bean Rolls (1963), a tea canister containing loose dry beans and small paper scrolls printed with bean imagery and trivia (prefiguring her Bean Bag of 1978). Referencing the vitalist material philosophy of Jane Bennett (), Aurelie Matheron has argued that in works like Proposition #2, Knowles “conditions the durability of her performance to the inevitable decay of biological material.” The work subtly critiques our common regard of food as a form of immanent waste, turning this around so that “what has been discarded matters again” (, 107, 103). Like Proposition #2, The Identical Lunch—performable by almost anyone—turns food preparation and consumption into a special, mindful experience. This is convincingly illustrated by Journal of the Identical Lunch (fig. 4.4), an artist’s book chronicling performances of the piece, which details interactions with a particular waitress at Riss Diner in midtown Manhattan where the meal was originally eaten (). We quickly learn that the lunch is about more than simply a sandwich, as the seemingly straightforward recipe produces endlessly indeterminate results choreographed by the restaurant staff as unwitting performers alongside Knowles. The ephemeral foodstuff that inevitably ends up as human waste is revealed as a medium that brilliantly highlights the typically invisible, unheralded labor and care behind its preparation.

Figure 4.3

Figure 4.3 Figure 4.4

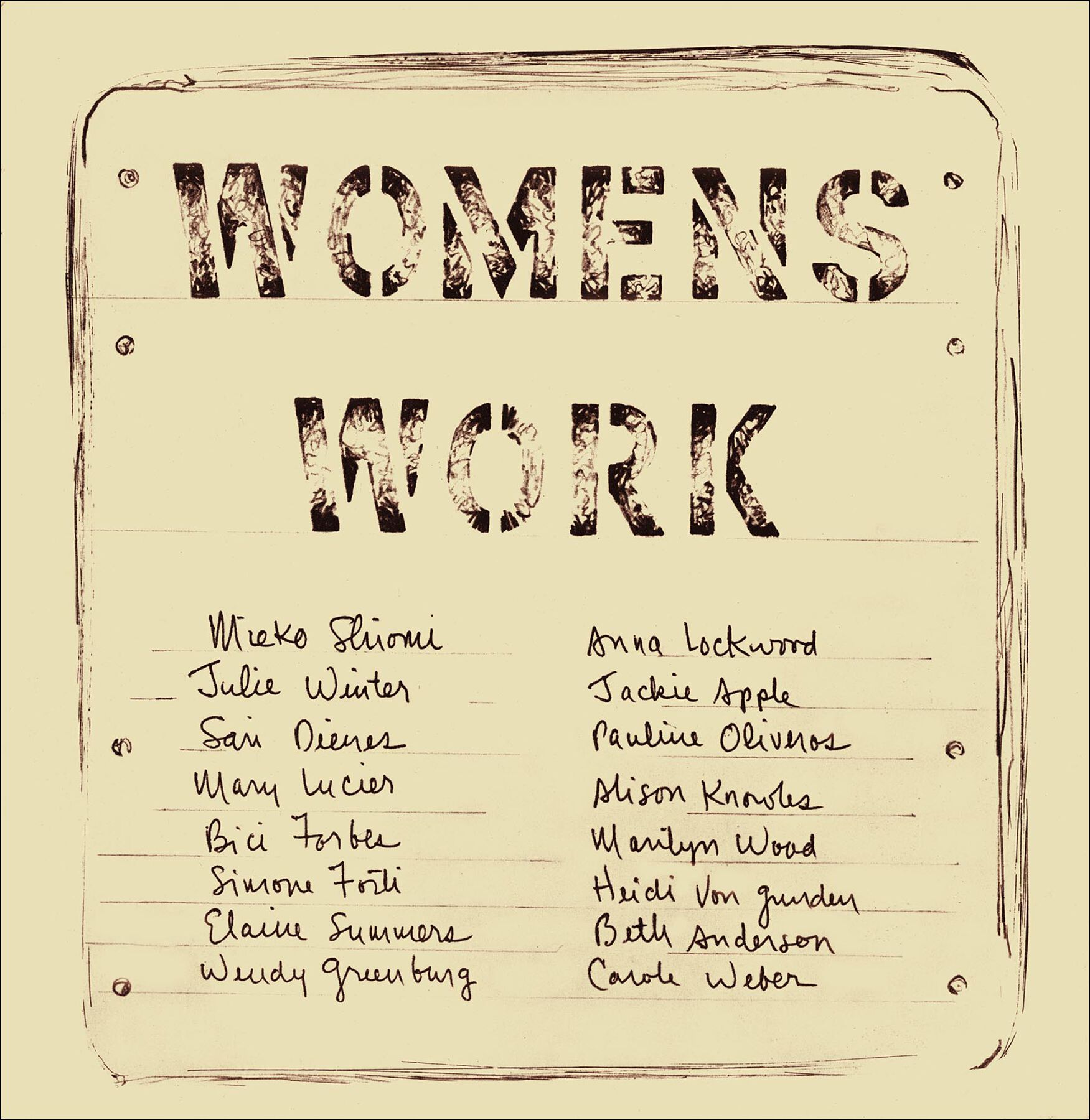

Figure 4.4Knowles’s work further reveals to us the degree to which notions of the everyday are entangled with what is conventionally understood as women’s experience or women’s work. As part of a collaborative publishing practice that has involved Marcel Duchamp, John Cage, Pauline Oliveros, and, more recently, Rirkrit Tiravanija (another famous food artist), in 1975 Knowles coedited with composer Annea Lockwood the anthology Women’s Work (fig. 4.5). A collection of experimental scores written by woman-identifying artists, Women’s Work followed the upswell of second-wave feminism and more than a decade’s worth of new performance practices exploring alternative approaches to scores. The anthology identified the correlations between experimental music’s phenomenology of heightened awareness, an ethics of noticing and care, and female labor. Its title thus carried a double meaning, as both an anthology of compositions by women but also pieces that paid attention to so-called women’s work as worthy of appreciation and an art form in itself. Knowles and Lockwood’s project anticipated the trenchant arguments of anthropologist and labor theorist David Graeber, who has said, “We need to start by redefining labor itself, maybe, start with classic ‘women’s work,’ nurturing children, looking after things, as the paradigm for labor itself and then it will be much harder to be confused about what’s really valuable and what isn’t” (, my emphasis). In the realm of art, the kinds of socially oriented, participatory, communitarian activities that are celebrated under the terms of relational aesthetics or social practice may be viewed as simply reframing what has been traditionally considered women’s work, long undervalued while being absolutely essential to the functioning of society.

Figure 4.5

Figure 4.5By recasting women’s work as performance art, Knowles collapsed the roles of performer and caregiver, making the experience of women’s work available to diverse others. Like the “maintenance art” of Mierle Laderman Ukeles, her gestures elevated to the level of art the mundane work by which women’s time and energy is already consumed. In using the score format in conjunction with biological materials, however, further elisions take place once such pieces enter museum collections, with the roles of performer, beholder/participant, curator, and conservator equalizing to a remarkable degree. Engaging with Knowles’s work, all partake, for example, in the making and eating of a salad or a simple lunch. For curators and conservators, minding the work of art becomes a form of domestic labor transferred to the workplace, inviting us to notice the ways in which the practical and disciplined care of arts professionals is fundamentally gendered, aligned with what we traditionally think of as women’s work regardless of whether or not that work is performed by those who identify as women.

If Knowles’s Fluxus practice resonated with concerns of both the feminist and the environmentalist movements unfolding contemporaneously in the 1960s, by the 1970s her imbrication of female-associated forms of caregiving, management of biological processes and materials, and acceptance of metabolic decay as a fundamental condition of life resonated with the emerging discourse of ecofeminism. From its beginnings in the mid-1970s, ecofeminist theory and activism have strengthened connections between feminism, environmentalism, and broader social justice struggles by identifying the parallels among marginalized human populations, on the one hand, and on the other, entities in and of nature that have been marginalized, colonized, polluted, or otherwise exploited (; ). As a vibrant, evolving discourse, ecofeminist frameworks and methodologies have since aligned with renewed awareness of Indigenous and racialized knowledge and the decentering of anthropocentric frameworks in favor of new materialisms and object-oriented ontologies. The ecofeminist ethic of Knowles’s work—its attention to and care for biological matter, its radical empathy with nature—means that “the work” in both its material and processual dimensions (the physical artwork and the labor that sustains it) do not end. Such an approach opposes the techno-futuristic aesthetic of artists such as ORLAN or Stelarc, whose work typically comes to mind when we think of contemporary bioart and its approach to living matter, which seeks to artificially extend life through complex technological, genetic, or other biological modification. Taking a different tack, Fluxus artists have paid attendant, appreciative witness to ruin, occupying us with quite simple means of caring for and maintaining the material world and its beings while simultaneously accepting the fate of their degradation and decay.

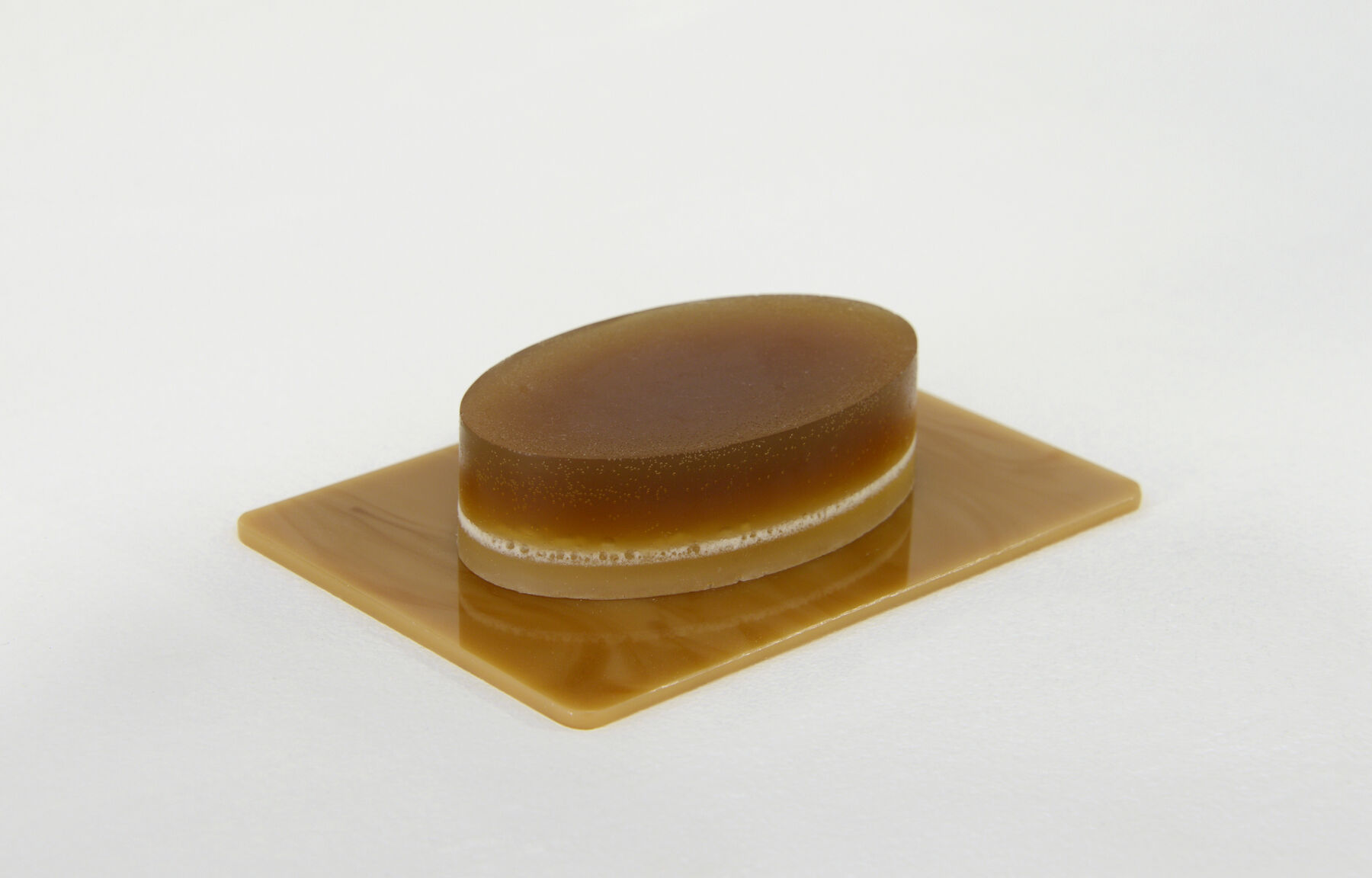

If, as an avant-garde, Fluxus was invested in integrating art into everyday life, its food objects understood life in terms of biotic networks. As such, Fluxus food art’s embrace of metabolic transformation and ruin stands as a compelling precedent (one perhaps more appropriate than bioart’s speculative science) for a number of contemporary art practices that employ biological materials in ways that similarly honor the aesthetics of decay and take this as the basis for multispecies collaborations. One thinks, for example, of Jae Rhim Lee’s Infinity Burial Suit (2008–ongoing, fig. 4.6), a jumpsuit adorned with mushrooms that have been adapted to consume the wearer’s hair, nails, and skin, such that upon death, their body will be actively broken down and returned to soil by the bespoke fungi. Or Anicka Yi’s experiments with mold as a material, including in sculptural works such as Grabbing at Newer Vegetables (2015, fig. 4.7), which utilizes bacteria collected from the artist’s network of female friends and colleagues to cultivate gorgeous, grotesquely fascinating messages and visual designs. Other artists, including Kelly Kleinschrodt and Emily Peacock, have embedded human-generated biological materials in soap-based artworks that explicitly link living matter with performative gestures of care and remembrance. Kleinschrodt’s soaps, made with the artist’s own breast milk, translate intersubjective maintenance acts of nutrition and hygiene into the form of beautiful objects for contemplation that are also extremely vulnerable to their environment (fig. 4.8). Peacock’s soaps, poured into simple marble vessels, cradle within them amounts of her son’s umbilical cord and placenta, her husband’s hair, and her mother’s cremated remains, looking generationally both forward and back to metabolic processes of the individual body that reach beyond the self to entangle others (fig. 4.9). These works remind us of the always astonishing proximity of caregiving and death. With exquisite tenderness, they acknowledge the entropic inevitability that we (and they) will perish someday. At the same time, fittingly, their deliberate fragility activates a circuit of care for the object that mirrors the very activities that inspired their creation.

Figure 4.6

Figure 4.6 Figure 4.7

Figure 4.7 Figure 4.8

Figure 4.8 Figure 4.9

Figure 4.9The anthropologist Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing has illuminated parallel dynamics in her ethnography of the communities of foragers and dealers that have sprung up around the wild harvesting and trade of the treasured matsutake mushroom, which thrives in forests (of Oregon, China, Japan, and beyond) that have been ruined by the logging industry. In late or post-capitalist/industrial landscapes of “transformative ruin,” it is only “assemblages of species” that survive because they have adapted via “contaminated diversity,” a paradoxical form of enrichment in the wake of pollution. She writes, “Staying alive—for every species—requires livable collaborations. Collaboration means working across difference, which leads to contamination.” In addition to foregrounding symbiosis as the rule of nature and not the exception, Tsing further argues that “precarity is the condition of our time” (, 28, 20, emphasis in original). With it comes indeterminacy, or the unplanned nature of life’s unfolding through time. Although indeterminacy is often frightening, she reminds us that “indeterminacy also makes life possible” (, 20, my emphasis).

A more recent anthology coedited by Tsing, Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet (2017), opens with an illustration of an indeterminate musical score by John Cage, an experimental composer and progenitor of Fluxus. The work, Fontana Mix (1958), is in fact composed of overlaid transparencies that combine a tightly gridded rectangle with a wild web of curved lines and a fixed constellation of individual dots. In the context of Tsing’s volume, the curious graphic suggests how, in nature, infinite forms of indeterminacy are achieved through the overlay of multiple life systems or ecologies: humans, individual animals, plants, environments, and atmospheres or microclimates. But we might also relate this model to the indeterminacies that arise when artworks rendered in diverse materials encounter and move through various institutional systems, populated by human actors with all their individual investments. Tsing and her coauthors argue that “to survive, we need to relearn multiple forms of curiosity” and become experts in the art of noticing, attuned to the complexity of “multispecies entanglement” (, G11). In the development of organisms—and, arguably, human culture too—nature selects and privileges successful relationships rather than singular individuals or entities. Correspondingly, the radical forms of multispecies collaboration that define living-matter artworks render obsolete our conventional notions of the autonomy of the work of art. Thus it may help us in our work (as conservators, curators, scholars, or otherwise) to understand collaboration as extending not only to our near-at-hand colleagues but also to the very materials with which we are dealing, including their inherent microbial agents. With the aforementioned examples in mind, especially the signal work of Knowles, the ecofeminist ethic behind this work demonstrates that the artwork reconceived as an eternal metabolic network haltingly lives on—not despite but because of the collaborative proposition of its ongoing decay, transformation, and regeneration (fig. 4.10).

Figure 4.10

Figure 4.10Notes

This term adapts the language of Fluxus affiliate Robert Filliou, who once imagined all conceptual artists to be participants in a global “eternal network” of “permanent creation,” which links all their actions—artistic and nonartistic, well and badly executed—into a continuous creative gesture (). ↩︎

Email from Benjamin Patterson to the author, November 30, 2009. ↩︎

Bibliography

- Adams and Gruen 2014

- Adams, Carol J., and Lori Gruen, eds. 2014. Ecofeminism: Feminist Intersections with Other Animals and the Earth. New York: Bloomsbury.

- Bennett 2010

- Bennett, Jane. 2010. Vibrant Matter. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Fredrickson 2019

- Fredrickson, Laurel Jean. 2019. “Life as Art, or Art as Life: Robert Filliou and the Eternal Network.” Theory, Culture & Society 36 (3): 27–55.

- Graeber 2014

- Graeber, David. 2014. “Spotlight on the Financial Sector: Did Make Apparent Just How Bizarrely Skewed Our Economy Is in Terms of Who Gets Rewarded [interview with Thomas Frank].” Salon, June 1, 2014, https://www.salon.com/2014/06/01/help_us_thomas_piketty_the_1s_sick_and_twisted_new_scheme/.

- Harren 2016

- Harren, Natilee. 2016. “The Provisional Work of Art: George Brecht’s Footnotes at LACMA, 1969.” Getty Research Journal, no. 8, 177–97.

- Harren 2020

- Harren, Natilee. 2020. Fluxus Forms: Scores, Multiples, and the Eternal Network. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Higgins 2011

- Higgins, Hannah. 2011. “Food: The Raw and the Fluxed.” In Fluxus and the Essential Questions of Life, edited by Jacquelynn Baas, 13–21. Hanover, MA: Hood Museum of Art.

- Hölling 2015

- Hölling, Hanna. 2015. Revisions—Zen for Film. New York: Bard Graduate Center.

- Hölling 2017

- Hölling, Hanna. 2017. Paik’s Virtual Archive: Time, Change, and Materiality in Media Art. Oakland: University of California Press.

- Joselit 2013

- Joselit, David. 2013. “The Readymade Metabolized: Fluxus in Life.” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, nos. 63/64, 190–200.

- Knowles 1971

- Knowles, Alison. 1971. Journal of the Identical Lunch. San Francisco: Nova Broadcast.

- Matheron 2019

- Matheron, Aurelie. 2019. “Performing Waste, Wasting Performance: The Ecology of Fluxus.” Resilience: A Journal of the Environmental Humanities 6 (1): 102–17.

- Patlán 2010

- Patlán, Lorena. 2010. “Career Profile: Albrecht Gumlich, Objects Conservator.” Iris: Behind the Scenes at the Getty, November 24, 2010, http://blogs.getty.edu/iris/career-profile-albrecht-gumlich-objects-conservator/.

- Robinson 2004

- Robinson, Julia. 2004. “The Sculpture of Indeterminacy: Alison Knowles’s Beans and Variations.” Art Journal 63 (4): 96–115.

- Tsing et al. 2017

- Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt, Heather Swanson, Elaine Gan, and Nils Bubandt, eds. 2017. Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Tsing 2015

- Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Warren 1997

- Warren, Karen J., ed. 1997. Ecofeminism: Women, Culture, Nature. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Woods 2014

- Woods, Nicole L. 2014. “Taste Economies: Alison Knowles, Gordon Matta-Clark and the Intersection of Food, Time and Performance.” Performance Research: A Journal of the Performing Arts 19 (3): 157–61.